Liu Kang concludes his review of the 1970 exhibition with a question, albeit posed in a rhetorical manner, to signal the complexity involved in appreciating Eng Teng's oeuvre. Chia Wai Hon, on the other hand, acclaims Eng Teng's versatility as an inherent, defining aspect of his artistic methodology; what is more, he assigns specific goals for the preferred method:

Self-expression, more than anything else, drives him to search for inner satisfaction in clay, terra-cotta, ciment fondu, oil, water-colour, pencil and charcoal. He is no dabbler who tries his hand at various media just for the sake of doing something. He works exhaustively in one medium getting the most out of it before he moves on to another. (A Personal View of Eng Teng)

Wai Hon sees purpose and deliberateness in Eng Teng's employment of diverse materials and processes. He insists that the artist does not deal with them unthinkingly; he certainly does not do so merely to register difference or to flaunt his abilities. He then proceeds to identify an aesthetic ideology fuelling these varied engagements, calling it "self-expression". Furthermore, this ideology has a psychological resonance in that it is driven by a "search for inner satisfaction". As a diagnosis where is it leading to? Wai Hon tries to explain Eng Teng's versatility in terms of deeply lodged drives which can only be accommodated by a range of multi-media activities; in other words, any one medium is insufficient, too limited in scope, to satisfactorily embody, express the depth of his intentions and the richness of his thoughts. Needless to say, these dispositions are not peculiar to Eng Teng; what is clear though, is that he exemplified them with degrees of consistency, rigour and accomplishments unmatched by anyone else in Singapore. Hence the acclaim and also the difficulties encountered in critically evaluating his efforts. The literature on art in Singapore has been shaped chiefly to deal with painting; so much so that in meeting an artist such as Eng Teng, writers experience awkwardness in discussing works which are beyond the pale of painting. This is especially so in the case of sculpture. An interesting situation arises, namely: while Eng Teng's entry and re-entry into the art world here are applauded, and while his sculptural and ceramic creations are hailed as breaking new ground, they also bring into the limelight the limits of critical enterprise in Singapore.

Towards the end of Wai Hon's appraisal cited above, reference is made to a chronological scheme within which the development of Eng Teng's practice can be [83/84] appraised; this is directed particularly to the use of various media. The scheme is mapped clearly and precisely:

He works exhaustively in one medium getting the most out of it before he moves on to another. Thus at one stage clay would serve him as a vehicle of expression for an idea that he wishes to work out. He does variations and experiments on the theme using one medium until be is satisfied that he has exploited it to the utmost. Then, and only then, will he switch over to something else.(Ibid.)

Wai Hon perceives a temporal, linear sequence in Eng Teng's approach to materials and processes; accordingly, he is seen as preoccupied with one medium or process at a time, exploring its potential and shifting interest to another only after exhausting all possibilities. Yet, this study has shown Eng Teng embarking upon multi-media engagements simultaneously and from the very onset. Throughout his formal education in Singapore and in England, he continued with his activities in areas beyond the requirements of his curriculum; hence, while in NAFA he produced sculptural works although painting and drawing were his major study areas. And in England, he sustained his interest in painting and drawing even as his principal studio subjects were in pottery. In describing his outlook Eng Teng emphasises its diversity as well as the tendency to be concurrently active in more than one direction or arena:

I am not set in one direction. I reach into many different paths at one time. I don't know whether this is good or bad. I just can't stay put in one single position too long because I get tired of it. (3 Dialogues, p. 26.)

In this connection the exhibition of 1970 is of particular significance because it displayed works emerging from his practice at its widest scope. Subsequently he narrowed the range of involvement; increasingly the focus was on sculpture and pottery, Eng Teng almost ceased to produce paintings on his return to Singapore in 1966; such drawings that he executed were undertaken chiefly as studies for sculptural works and projects or of forms with three-dimensional destinations. The public reception of this exhibition underlined the attention paid to sculptures in the show; indeed, reports in the mass media focused on this medium exclusively, highlighting the emotional tenor of the compositions.4 In this regard mention has been made of the tendency of writers on Eng Teng to give prominence to his sculptural works, even though his paintings and drawings were acknowledged as excellent and equal to those by any painter; reasons for this partiality have been offered.

Whereas in his assessment of the 1970 exposition Liu Kang singles out Epstein as an important influence on Eng Teng, Wai Hon, however, frees him from any historical connection or lineage; instead, he salutes Eng Teng's individuality to the extent of claiming a position of absolute autonomy:

It is Eng Teng's belief that an artist should not be contented with echoing somebody's ideas all the time. Hence it is that in Eng Teng's work one finds it difficult to point to the influence that is at work, He professed an admiration for Epstein, and yet traces of this sculptor's influence are hardly noticeable if any do exist. Eng Teng enjoys being himself in his work. (A Personal View of Eng Teng)

The art historical lineage of an artist is a complex issue; and in particular instancesthe imprints of a genealogy may well be faint or diffused. Furthermore, there are artists who camouflage their antecedents, refer to them obliquely or even deny them. But this is not to say that an artist is free of connections with his/her contemporaries, and with artists and art of the past. Artists do not and cannot practice in a vacuum. Eng Teng points to a number of modern sculptors whom he has looked at closely and admired. "I admire Rodin and later on Jacob Epstein. Epstein's works are very emotional and powerful. And then I admire Manzu, Giacometti and Brancusi for concentration and simplicity. As for Henry Moore, well I am getting a little tired of his work." (6 Dialogues, p. 47-48.) He covers a wide terrain, selecting preferred characteristics or values; it will be difficult to stitch these together into forming a coherent map. It will also be difficult to isolate any of these references and see them manifested technically or formally in Eng Teng's compositions. Yet, there are echoes of Epstein which are integrated into some of his figurative schemes. There also are adaptations of Moore's curvaceous forms despite his professed declining interest in that artist. The connections can be appreciated along generally shared aesthetic goals or dispositions as well. Indeed, having studied in England in the early 1960s, it would have been extremely difficult to avoid the weighty, rampant influence of Epstein and Moore; they were the dominant figures in the sculptural world. In all these respects, it is interesting to juxtapose Wai Hon's view with that advanced by Ma Ge; in describing the development of Malayan art (an inclusive designation encompassing Singapore as well) and turning to aspects of sculpture, he makes the following observation; "Having a similar style to Lim Nan Seng is Singapore's Ng Eng Teng."(Ma Ge, p. 82.) It is clear that the provision of art historical frames for appreciating Eng Teng's practice is by no means settled.

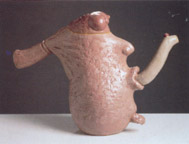

Wai Hon characterises the individuality or distinctiveness of Eng Teng's sculptures by drawing a parallel between his pottery and the three-dimensional compositions. "Eng Teng's figures are the direct influence of his involvement in pottery. The pot-bellied shape appeared time and time again in a variety of figurines and large sculpture."(A personal View of Eng Teng) Wai Hon was the first to suggest a direct, causal link between Eng Teng's pottery and his sculpture; it is a view repeated by commentators subsequently, and almost without exception. So much so, it is an opinion that has become axiomatic.

Whereas Wai Hen distinguishes Eng Teng's sculpture by pointing to the influence of pottery, Liu Kang discusses a number of formal features without characterising them as derivations; on the contrary, he implies that they are universal, the hallmarks of accomplished artists and of works that have attained quality or excellence. The majority of the productions in the 1970 exhibition, observes Liu Kang, "explore the rhythm of pure lines, contrasts between solid and void, interplay of three-dimensional forms, as well as overall presentation of beautiful forms,"(Liu Kang, The Multi-Talented Ng Eng Teng) As attributes they are among the criteria used in appraising sculpture; as properties they are fundamental in the making or creation of sculpture. That is, with the possible exception of "the presentation of beautiful forms" as a necessary attribute; as an ideal it may not be generally shared or supported although "presentation" as a principle is extremely important.

In discussing Aboriginal Woman, Singapore Girl and Miss Vogue in Chapter 1, attention was paid to those very attributes/properties singled out by Liu Kang. In them, lines had a number of functions; lines as contours determined the limits of solids and shapes. Lines as marks on surfaces and planes appeared in a variety of relationships such as linear arrangements or rhythmic indentations, as in the relief composition titled Miss Vogue. In dealing with Aboriginal Woman its forceful presence was highlighted; this was achieved by the choice of a dominant viewpoint. This in turn generates and governs the plasticity of the composition, the way it displays its three-dimensional formation and the way it relates to its environment. All these can be seen to satisfy the promotion of the "presentation of forms" as a criterion in appreciating Eng Teng's work. Of course this aspect is not particular to this composition but one which stimulates the production and apprehension of his sculptural oeuvre. Liu Kang also refers to "the interplay of three-dimensional forms"; this is of cardinal importance in modern sculptural thinking and making, and the hallmark of an advanced, sophisticated practice.

In discussing Aboriginal Woman, Singapore Girl and Miss Vogue in Chapter 1, attention was paid to those very attributes/properties singled out by Liu Kang. In them, lines had a number of functions; lines as contours determined the limits of solids and shapes. Lines as marks on surfaces and planes appeared in a variety of relationships such as linear arrangements or rhythmic indentations, as in the relief composition titled Miss Vogue. In dealing with Aboriginal Woman its forceful presence was highlighted; this was achieved by the choice of a dominant viewpoint. This in turn generates and governs the plasticity of the composition, the way it displays its three-dimensional formation and the way it relates to its environment. All these can be seen to satisfy the promotion of the "presentation of forms" as a criterion in appreciating Eng Teng's work. Of course this aspect is not particular to this composition but one which stimulates the production and apprehension of his sculptural oeuvre. Liu Kang also refers to "the interplay of three-dimensional forms"; this is of cardinal importance in modern sculptural thinking and making, and the hallmark of an advanced, sophisticated practice.

Growth Form, 1962 Figs. 86a, b is composed with interests such as these in mind; indeed,in many respects it marks a significant departure from the images mentioned above and from the figurative compositions which dominate the early years of his development. A spherical form has been split into two segments; although they are connected towards the bottom, they are separated to accommodate space between them. In this intervening gap is inserted a wedge-shaped form which rises into the air steeply and is tilted away from the alignment of the two segments. The entire composition sits directly on the floor.

Growth Form, 1962 Figs. 86a, b is composed with interests such as these in mind; indeed,in many respects it marks a significant departure from the images mentioned above and from the figurative compositions which dominate the early years of his development. A spherical form has been split into two segments; although they are connected towards the bottom, they are separated to accommodate space between them. In this intervening gap is inserted a wedge-shaped form which rises into the air steeply and is tilted away from the alignment of the two segments. The entire composition sits directly on the floor.

It can be viewed as an entity bursting or opening to enable the birth and emergence of a new existence, which is beginning to exert its autonomy or separateness, Such a reading arises from associating suggestions springing from the title with evocations from the arrangement of the interlocking components. The composition is executed confidently and with clearly wrought purpose. It is the outcome of reconsidering the foundational notions and values of sculpture in Singapore; in this regard it is a production with radical implications.

Growth Form can be claimed to be one of the earliest non-representational sculptures produced in Singapore, although it is not the only one created by Eng Teng during this phase of his practice; it is non-representational in the sense that it is not concerned with the human figure which is the dominant interest of those who produce sculpture here. However, its radicality is not determined merely by this designation; there are deeper issues. Sculpture in its most pervasive manifestation assumes the condition of a monolith; a sculpted form appears and appeals as a compact body of mass and volume in space- It stakes its presence as a self-contained whole by its weight, stability and by securing a privileged ground. Eng Teng alters or interrogates these premises; or, and to say it differently, in Growth Form he examines these premises and explores alternative ways of producing and viewing sculpture. The most significant innovations in his practice and in the story of sculptural activity in Singapore are to be seen in the treatment of the monolith and the elimination or omission of the base.

The monolith is by no means the defining condition of sculpture in a remote past; in the hands of Brancusi at the beginning of this century it gained fresh formal relevance and novel symbolic force. By means of single-minded concentration on mass and volume, Brancusi created compact forms of rigorous simplicity, whose appeal was universal and unrivalled. His approach and works established a tradition in modern sculpture; Eng Teng would have encountered Brancusi in publications on sculpture which were indispensable in furnishing resources for his development. Indeed, in disclosing his esteem for Brancusi, Eng Teng singles out "concentration and simplicity" as the abiding attributes for his consideration. And there are productions in which the notion of sculpture in its embryonic form, or as Eduard Trier describes this approach as leading to the creation of "kernel sculpture", is powerfully realised., (Trier, p. 12.) Two Forms (Fig. 71), which was discussed in the preceding chapter, vividly displays Eng Teng's absorption of this conception of sculpture; each of the two formal components is compact, solid, shut in on all sides and self-contained.

The monolith is by no means the defining condition of sculpture in a remote past; in the hands of Brancusi at the beginning of this century it gained fresh formal relevance and novel symbolic force. By means of single-minded concentration on mass and volume, Brancusi created compact forms of rigorous simplicity, whose appeal was universal and unrivalled. His approach and works established a tradition in modern sculpture; Eng Teng would have encountered Brancusi in publications on sculpture which were indispensable in furnishing resources for his development. Indeed, in disclosing his esteem for Brancusi, Eng Teng singles out "concentration and simplicity" as the abiding attributes for his consideration. And there are productions in which the notion of sculpture in its embryonic form, or as Eduard Trier describes this approach as leading to the creation of "kernel sculpture", is powerfully realised., (Trier, p. 12.) Two Forms (Fig. 71), which was discussed in the preceding chapter, vividly displays Eng Teng's absorption of this conception of sculpture; each of the two formal components is compact, solid, shut in on all sides and self-contained.

In Growth Form, on the other hand, the solid volume has been opened up; the selfcontained monolith has given way to a composition made up of the aggregate of formal units and properties. What is more, sculpture is no longer characterised only by solidity, only by an enclosed body of mass and volume, but by the interlocking or interpenetration of a number of elements. Growth Form embodies solid and space, mass and void, and outer and inner volume. Simplicity has been replaced by complexity; self-containment is substituted with an ordering of components in which some are dominant and others subordinate. By opening the compact form, space enters into the configuration and assumes a positive, integral role in the design of the work. The intervening space acts as a bridge connecting the two spherical components; it also produces a variety of cast shadows, illuminating and darkening the outer and interior surfaces in shifting intensity. The insertion of the wedge-shaped form generates complexities; for instance, the curvaceous contours of the spherical components are disrupted. The vertical thrust of this form counters, even competes with, the stability evoked by the rounded forms. The sense of homogeneity, which would have prevailed if the monolith had been safeguarded, is compromised; in its stead appear shapes which vie for attention and arrangements consisting of jostling units. These interests, even as they are different or separate, do not evoke disquiet or point to agitated situations; on the contrary, the individual components are carefully controlled; their relationships are measured. Growth Form conveys settled presences.

At the beginning of the discussion of this composition I remarked that Growth Form breaks new ground in sculptural practice in Singapore by breaching two foundational premises distinguishing sculpture as an art medium. The first has to do with the monolith and it has been dealt with; the second is directed towards the base or, more precisely, its elimination. The base is a convention by which a sculpted image secures a ground amidst the surrounding reality and is firmly Tooted in it; it is also a device by which the sculpted image is segregated from its environment. Oddly, it is this dual aspect which projects the image as having an existence and a presence of its own. Jack Burnham underscores the primacy of the base when he observes that it "helps to create an aura of distance and dignity around the favoured object."11

Throughout the twentieth century, artists have relooked at and rethought the function of the base; a number of strategies were initiated to invest it with new values or to eliminate it altogether. There also emerged yearnings to free sculpture from the confines of gravity and set it air-borne. These endeavours widened the scope for sculptural activity immensely and, at times, resulted in the submission of bewildering productions for consideration as sculpture; these endeavours also severely tested and "undermined the protocol of the viewer-object relationship."(Burnham, p. 43.) So much so that in reviewing the condition of sculpture in 1964, Herbert Read was forced into adopting a dispirited stance and expressed his view in the following way:

One must ask a devastating question: to what extent does the art remain in any traditional (semantic) sense sculpture? From its inception in pre-historic times down through the ages until comparatively recently sculpture was conceived as an art of solid form, of mass, and its virtues related to spatial occupancy.(Read, p. 250.)

The sculpture that was produced after World War II struck Read as having abandoned these goals; for him, the art was reduced to nothing more that "a scribble in the air "(Ibid.) If questioning the definition of an art medium was debilitating for Read in the mid 1960s, it is now the norm; interrogation is intrinsic to any discourse. Of course Read's vision is fuelled by an ideal view of art, one which strenuously rejects the contamination of art by extraneous forces such as technology, popular culture, concepts and ideas emerging from diverse lived experiences. Not everyone subscribes to such a vision.

By eliminating the base and placing Growth Form directly on the floor, Eng Teng induces a pronounced degree of casualness in the relationship between the object and the viewer. In siting it on the floor, the earlier obligation to position the sculpted image at the standing eye-level of the viewer is by-passed. An immediate consequence is to bring the work closer to the flux of life and dismantle the hierarchical ordering of its presence. The viewer can forge direct connections with the object without observing the norms of propriety. Whereas in the sculpted figure perched on a pedestal of base the spectator-image association is governed by conventions of presentation and seeing, in the case of the object placed on the floor, such patterns can be cast aside. Fixed modes are replaced by fluid relations, and even happenstance.

In all these respects Growth Form establishes an important milestone in Eng Teng's artistic development as well as in the history of sculpture in Singapore. Eng Teng seized upon them as arenas that can be prospected. He did so with the aim of varying the, presentational aspects of sculpture, constantly reconsidering the parameters for viewer-figure interconnections. He did so in order to extend, tender flexible the boundaries of sculpture, so that the art of projecting bodies in space is imbued with fresh purpose and meaning.

I have dwelt at length on Growth Form because of its innovative status; in teasing out some of its novel features and sketching their implications, the criteria for considering works produced along comparable lines have been established, thereby facilitating their discussion. In dealing with this production at such length and in enlarging the terrain for its interpretation, it might be construed that Eng Teng's sculptural intentions are framed by the consequences teased from this work; the impression may be gained that his aims are directed chiefly towards substituting traditional values with new or alternative ones. This is not the case. In this connection it has been remarked that Eng Teng's practice is characterised by a plurality of approaches and engagements. His versatility surfaced at the very beginning and has persisted throughout his artistic development until the present; it is an attribute encompassing a variety of media and processes, as well as concepts and presentational aspects.

The earliest sculptural productions in this collection demonstrate Eng Teng's attempts at gaining familiarity with the language of modern sculpture; he does so by turning to a number of sources, examining them carefully, adapting and incorporating them into his scheme of creativity. Even as these are exploratory, and in some instances tentative, they embody the ideals articulated by Herbert Read, namely: sculpture conceived as "an art of solid form, of mass, and its virtues related to spatial occupancy." In Sorrow, c.1959 (Fig. 87) his reading of Rodin's use of the partial figure for intense dramatic purposes is acute and deep. The limbless, bust-length female figure strains as if seeking to release itself from a state of entrapment; it is a conception of struggle which features prominently in his figurative compositions. The head is tilted; the eyes are wide open while the mouth is parted, gasping for air. The neck is stretched and elongated to an unbearable degree; the breasts slope downwards, countering and responding to the pressure imposed by the outstretched neck. The hair is swept back and discreetly coiled, revealing the heightened expressivity of the head and neck. Sorrow can be viewed as signalling Eng Teng's tribute to Rodin; in paying homage to one of the fountainheads of modern sculpture, he declares one branch of his artistic lineage.

The earliest sculptural productions in this collection demonstrate Eng Teng's attempts at gaining familiarity with the language of modern sculpture; he does so by turning to a number of sources, examining them carefully, adapting and incorporating them into his scheme of creativity. Even as these are exploratory, and in some instances tentative, they embody the ideals articulated by Herbert Read, namely: sculpture conceived as "an art of solid form, of mass, and its virtues related to spatial occupancy." In Sorrow, c.1959 (Fig. 87) his reading of Rodin's use of the partial figure for intense dramatic purposes is acute and deep. The limbless, bust-length female figure strains as if seeking to release itself from a state of entrapment; it is a conception of struggle which features prominently in his figurative compositions. The head is tilted; the eyes are wide open while the mouth is parted, gasping for air. The neck is stretched and elongated to an unbearable degree; the breasts slope downwards, countering and responding to the pressure imposed by the outstretched neck. The hair is swept back and discreetly coiled, revealing the heightened expressivity of the head and neck. Sorrow can be viewed as signalling Eng Teng's tribute to Rodin; in paying homage to one of the fountainheads of modern sculpture, he declares one branch of his artistic lineage.

In the Head of John the Baptist, c. 1960-61 (Fig. 88) Eng Teng steps further back into the history of European art in order to register a range and depth of expressive modes; a possible source for this image are the relief carvings on French Gothic cathedrals. The Baptist is presented as a most austere man of the desert, who undergoes severe trials which test his entire being. John the Baptist is beheaded to satisfy Salome who asked for it as a reward for dancing for King Herod; it is a subject featured by a number of artists during the period of the Renaissance, the most renowned representation being the one by Donatello for the font in San Giovanni, Siena (completed in 1427). In Eng Teng's rendering, life appears frozen, terminated abruptly; the expressive resonances are forcefully inscribed and detailed. The mouth is gaping; the eyes are askew and drilled open. The skin on the checks and forehead is deeply furrowed and drained of all vitality. The expressive tenor is vividly registered on the surface; the treatment of the medium, however, is clumsy. Eng Teng employs a thick layer of clay, not as yet grasping the malleable, tensile properties of this material; in part this is the outcome of having to milise a crude variety of clay used primarily for the manufacture of bricks from the Alexandra Brickworks. In part this is a consequence of self-learning, of a procedure entailing trial-and-error, and not having the benefit of formal or systematic instruction.

In the Head of John the Baptist, c. 1960-61 (Fig. 88) Eng Teng steps further back into the history of European art in order to register a range and depth of expressive modes; a possible source for this image are the relief carvings on French Gothic cathedrals. The Baptist is presented as a most austere man of the desert, who undergoes severe trials which test his entire being. John the Baptist is beheaded to satisfy Salome who asked for it as a reward for dancing for King Herod; it is a subject featured by a number of artists during the period of the Renaissance, the most renowned representation being the one by Donatello for the font in San Giovanni, Siena (completed in 1427). In Eng Teng's rendering, life appears frozen, terminated abruptly; the expressive resonances are forcefully inscribed and detailed. The mouth is gaping; the eyes are askew and drilled open. The skin on the checks and forehead is deeply furrowed and drained of all vitality. The expressive tenor is vividly registered on the surface; the treatment of the medium, however, is clumsy. Eng Teng employs a thick layer of clay, not as yet grasping the malleable, tensile properties of this material; in part this is the outcome of having to milise a crude variety of clay used primarily for the manufacture of bricks from the Alexandra Brickworks. In part this is a consequence of self-learning, of a procedure entailing trial-and-error, and not having the benefit of formal or systematic instruction.

It was during his pupilage at Stoke-on-Trent and Farnham that Eng Teng gained knowledge of clay as a medium, and facility in employing it for industrial as well as artistic purposes. Even though his technical abilities were limited before this phase, it did not inhibit him from dealing with it. Through persistence and close study of precedents, he assembled a modest range of formal entities to suit his purpose, This is clearly seen in Singapore Girl which was discussed in Chapter I and illustrated as Fig. 9. As in Head of John the Baptist, this work is also marked by an awkward treatment of clay, and for similar reasons. Yet, the formal devices alleviate deficiencies emerging from inadequate handling of the material. Singapore Girl demonstrates affinities with Lim Nan Seng's compositions; this is especially evident in the drapery of the figure and in the modelling of the torso and head. Among the most prominent devices is the use of coiled and overlapping surfaces to evoke continuous flows of drapery folds; Eng Teng has grasped the potency of this device and has used it advantageously, intelligently. Nan Seng attained a pronounced degree of naturalism in his figurative compositions; this was realised by employing modulated planes which softly settled into assuming figurative forms; his figures appear to be vitalised by an inner force or inner life. The torso of Singapore Girl with its undulating surfaces and the smiling face comes close to embodying the values highlighted in Nan Seng's works.

One influence towers over all others in shaping the early phase of Eng Teng's sculptural practice; it can be traced to Jean Bullock. This is hardly surprising for it was she who provided him with the foundational knowledge of sculpture and introduced new materials for his consideration. Eng Teng met her through the agency of the British Council; they became firm friends. He describes the occasion vividly:

In 1959 1 had the good fortune to meet Jean Bullock who arrived with her British air force husband, John. Through the British Council, Jean approached to meet local artists who spoke English. Chia Yew Kay of the British Council introduced Jean Bullock to me. We became good friends. I used to get my nieces to pose and we worked together on developing sculptures featuring the head. I was learning and she was teaching me the finer aspects of sculpture making, I also helped her cast her works in ciment fondu concrete and in the process began to understand the material. I learnt a lot from her and consider her my teacher. If not for her I would not have been working in ciment fondu. I find ciment fondu a great material for sculpture, although it is industrial concrete and this puts people off it. (Conversation, p. 152.)

It was a mutually enhancing relationship and has endured until the present. Eng Teng identifies her as his teacher, emphatically; indeed, she was his only teacher in sculpture. He did not receive instruction from anyone else or from any other source. When lie enrolled in Farnham School of Art he declared his interest in sculptural studies and produced three-dimensional work while residing there; the supervision, however, was haphazard and ineffectual. Besides learning from her, Eng Teng and Bullock produced sculpture as fellow-artists; to this end, he enlisted his nieces to pose as models. The interest was in the head as an autonomous subject and an independent formal entity; in this regard the camaraderie between them was crystallised by the creation of portrait heads of one by the other (Fig. 90 [only sculpture of Jean Bullock by Ng Eng Teng shown]). Eng Teng also collaborated in projects initiated by Bullock and assisted in completing them; in this way he became familiar with ciment fondu which has remained as the preferred material for his sculptural productions.

It was a mutually enhancing relationship and has endured until the present. Eng Teng identifies her as his teacher, emphatically; indeed, she was his only teacher in sculpture. He did not receive instruction from anyone else or from any other source. When lie enrolled in Farnham School of Art he declared his interest in sculptural studies and produced three-dimensional work while residing there; the supervision, however, was haphazard and ineffectual. Besides learning from her, Eng Teng and Bullock produced sculpture as fellow-artists; to this end, he enlisted his nieces to pose as models. The interest was in the head as an autonomous subject and an independent formal entity; in this regard the camaraderie between them was crystallised by the creation of portrait heads of one by the other (Fig. 90 [only sculpture of Jean Bullock by Ng Eng Teng shown]). Eng Teng also collaborated in projects initiated by Bullock and assisted in completing them; in this way he became familiar with ciment fondu which has remained as the preferred material for his sculptural productions.

Bullock's influence on Eng Teng was transmitted by means of demonstrations; that is to say, teaching was conducted by extending her practice, by making Sculpture not in the privacy of the studio but in the open and in the presence of another. Such performative events are powerful means of conveying intentions and methods; and they endure. Eng Teng absorbed the objectives and procedures that he beheld. The aims of Bullock's instruction were twofold, namely: (a) to gain familiarity with materials, probing into their constitution and manipulative range or propensities; (b) to cultivate comprehensive knowledge of formal construction. The subject was the human figure with an emphasis on the head.

A graduate of Watford College of Art and Camberwell College of Art in London, Jean Bullock was an accomplished portrait sell plot at the time she arrived in Singapore, Her compositions are modest in size and even unprepossessing. On closer scrutiny, however, acuity of observation springs into relief and the detailed registration of expressive states or situations gain in intensity. She has produced a range of figurines and a substantial body of work featuring the head; the preference for the head is not unusual. The head is conceived as the confluence of the most complex psychological and physiological features that distinguish human beings; it is for this reason that it has assumed the status of a sovereign entity, especially in European art traditions, Even as it has an illustrious tradition, the interest in the head has not diminished; indeed, it has attained wide appeal amongst modern/ contemporary artists practicing in greatly differing cultural conditions, There is an additional factor to be considered; the autonomy of the head has been secured at the expense of the remainder of the body. This can be turned to advantage in those circumstances in which the representation of the body is regarded with anxiety and trepidation, Although Eng Teng is aware of such circumstances, he is not necessarily constrained by them.

In this collection there is a head, a remnant of a three-quarter length figure, which can be attributed to the phase when he was learning from and with Jean Bullock, Head of Paddy Boy, c. 1959 (Fig. 92); it is the only surviving work featuring the head executed at this time. The surface is untreated; the scum from the plaster of paris mould remains uncleaned. The main interest is in the modelling of the face, and the outcome is uneven; the ears and the nose are treated clumsily with inadequate comprehension of proportion and relationship. The eyes and the forehead, on the other hand, demonstrate sensitivity to formal arrangements and emotional resonances. The eyelids droop gently and curve over the eye; the forehead rises steeply, directly over the eyes and eyebrows, and then slopes gradually towards the hairline in a curving plane. Approached with emotional or psychological interests these details provoke thoughts on the fragile state of the young, and tile vulnerability of youth.

In this collection there is a head, a remnant of a three-quarter length figure, which can be attributed to the phase when he was learning from and with Jean Bullock, Head of Paddy Boy, c. 1959 (Fig. 92); it is the only surviving work featuring the head executed at this time. The surface is untreated; the scum from the plaster of paris mould remains uncleaned. The main interest is in the modelling of the face, and the outcome is uneven; the ears and the nose are treated clumsily with inadequate comprehension of proportion and relationship. The eyes and the forehead, on the other hand, demonstrate sensitivity to formal arrangements and emotional resonances. The eyelids droop gently and curve over the eye; the forehead rises steeply, directly over the eyes and eyebrows, and then slopes gradually towards the hairline in a curving plane. Approached with emotional or psychological interests these details provoke thoughts on the fragile state of the young, and tile vulnerability of youth.

Hock Tin, 1961 (Fig. 93), exemplifies formidable accomplishment in composing the head; in this work the influence of Bullock is apparent (see Fig. 89). The influence has also been absorbed and internalised, so much so that the image projects confidence and purpose as well as familiarity with the method of composition. This head can be viewed comparatively with his painted portraits of members of his family; as in them, here too Eng Teng deals with complexities arising from, familiarity (Hock Tin is his niece) and the need to maintain 6istance in Order to portray an image of another. The cheeks, chin and neck are modelled sensitively; the mouth is forcefully shaped with the lips curled and outlined clearly. The hair settles as a compact covering on the skull, is, wrapped over the sides and partially over the ears. The neck flares outwards indicating the shoulders and in this manner, reaches out into space; while the image is rooted in its base, it also is connected with its environment.

Hock Tin, 1961 (Fig. 93), exemplifies formidable accomplishment in composing the head; in this work the influence of Bullock is apparent (see Fig. 89). The influence has also been absorbed and internalised, so much so that the image projects confidence and purpose as well as familiarity with the method of composition. This head can be viewed comparatively with his painted portraits of members of his family; as in them, here too Eng Teng deals with complexities arising from, familiarity (Hock Tin is his niece) and the need to maintain 6istance in Order to portray an image of another. The cheeks, chin and neck are modelled sensitively; the mouth is forcefully shaped with the lips curled and outlined clearly. The hair settles as a compact covering on the skull, is, wrapped over the sides and partially over the ears. The neck flares outwards indicating the shoulders and in this manner, reaches out into space; while the image is rooted in its base, it also is connected with its environment.

In utilising ciment fondu, Eng Teng employs the method of modelling; it is a process which the material is given form and shape by gradual addition. The connection between the hand and the material is direct, persistent and consequential. Of course decisions can be made to brush or mute these marks so that they assume discreet registrations rather than leave ostensive imprints. In this work, as in all others in which ciment fondu is employed, Eng Teng prefers to smoothen the surface; he is, however, alive to the effects of textural variations and the drarnatic importance of light and shade. These are manifest in Hock Tin: the planes defining the cheeks are modulated so that shadows are cast on neighbouring surfaces while light is caught by surfaces meeting and softly rising into the air. The nose ridge and indented upper lip converge into a complex formation; here modelling takes on a characteristic and powerful function. These features are formed by thrusting, accumulated forces swelling outwards from the interior. In conveying such sensibilities Eng Teng has grasped the strength and form-giving proclivity of modelling.16 Cast shadows enliven the surfaces on the forehead and cheeks, emitting the sensation of life-forces stirring beneath and impinging upon the outer skin. The neck is dipped in shadow, emerging as a pillar, its volume rounded and firm, with immense strength to support the head and to hold it in a steadfast posture. In all these aspects Eng Teng displays his ability to deal with the conventions shaping the formal and psychological dimensions of portrait heads in sculpture.

In George, 1963 (Fig. 94), Eng Teng takes pains in detailing the appearance of the subject; this portrait head was produced while he was studying in Farnham School of Art. It is apparent that his involvement with life-drawing in this institution, which instilled in him the capacity to realise the figure as a concrete, tangible entity in formal terms, has affected his sculptural practice.In George The acuity of seeing, characteristised by registrations of detail, is transferred into sculptural form. Indeed, George can be compared with Rev. W. Short of Croydon (Fig. 78); the two portraits are distinguished by the sustained interest in physiological details as symbolising personality or a sense of psychological being.

In George, 1963 (Fig. 94), Eng Teng takes pains in detailing the appearance of the subject; this portrait head was produced while he was studying in Farnham School of Art. It is apparent that his involvement with life-drawing in this institution, which instilled in him the capacity to realise the figure as a concrete, tangible entity in formal terms, has affected his sculptural practice.In George The acuity of seeing, characteristised by registrations of detail, is transferred into sculptural form. Indeed, George can be compared with Rev. W. Short of Croydon (Fig. 78); the two portraits are distinguished by the sustained interest in physiological details as symbolising personality or a sense of psychological being.

Eng Teng pinches, gouges, depresses and raises the clay in order to shape the features and imbue them with individuality and a eyes are deep-set and quietly watchful; the mouth is settlec the upper lip gripping the lower and together inscribing a thin, curving line. The cheeks are pitted and wrinkled; the eyelids are folded heavily while the eyebrows are marked by incised furrows. The variegated surfaces which define the face are contrasted with the smoothened planes of the gently sloping forehead; these meet with the receding hair which is arranged in a compact mass. The collar and tie are forcefully designed and raised in high relief. Eng Teng manipulates clay effectively and purposefully; the features are studied closely and have been sensitively transformed through the medium to present an image of a person captured at a particular moment. The insistence on particularity leads Eng Teng away from idealised projections to deep considerations of the nature of specific bodies in specific time and space.

These are not momentary or contingent preoccupations. Of course facilities acquired between 1959-1964 attain maturity and are diversified in the 1970s; there also is an expansion of themes and a widening of symbolic interests over the years. Even so, and this has already been observed on a few occasions, concepts or compositions marking significant phases in his development resurface in subsequent years. When they do, at times the formal aspects are transformed only in detail while the scope of the content is deepened and intensified; at other times the recollection of earlier efforts provokes new, surprising departures, resulting in innovative productions. The head as a theme recurs periodically, and embodies a variety of formal and symbolic schemes. For the moment one such work is considered.

Ten years after he produced George, Eng Teng executed a portrait head each of his father and mother; Portrait Head of Mother, 1973 (Fig. 95) is in this collection while that of the father is with the artist. As with the image of George, here too there appear detailed depictions of physical features highlighting the outcome of ageing. The thinning hair is pulled tightly over the skull, and rendered as raised, uneven bands. The cheeks and forehead are wrinkled; the skin is in some sectors folded and sagging, and furrowed and shrunken in other sectors. Eng Teng has painstakingly inscribed the surface with a range of marks produced by varying the pressure applied by his hands on the material; the malleable nature of clay and ciment fondu permit the transfer of form-making from one to another effectively. Light skims over the surface, settling into pools of shadow in recesses and glinting when it catches a protruding surface; cast shadows and highlights evoke planes turning in space, thereby pointing to three-dimensional attributes or forms. Whereas George is cast with a severe demeanour, in portraying his mother, while maintaining a distance allowing him to observe and represent details of appearance scrupulously, Eng Teng also infuses the image with warmth and gentleness. Portrait Head of Mother imparts a contained, reflective presence.

Ten years after he produced George, Eng Teng executed a portrait head each of his father and mother; Portrait Head of Mother, 1973 (Fig. 95) is in this collection while that of the father is with the artist. As with the image of George, here too there appear detailed depictions of physical features highlighting the outcome of ageing. The thinning hair is pulled tightly over the skull, and rendered as raised, uneven bands. The cheeks and forehead are wrinkled; the skin is in some sectors folded and sagging, and furrowed and shrunken in other sectors. Eng Teng has painstakingly inscribed the surface with a range of marks produced by varying the pressure applied by his hands on the material; the malleable nature of clay and ciment fondu permit the transfer of form-making from one to another effectively. Light skims over the surface, settling into pools of shadow in recesses and glinting when it catches a protruding surface; cast shadows and highlights evoke planes turning in space, thereby pointing to three-dimensional attributes or forms. Whereas George is cast with a severe demeanour, in portraying his mother, while maintaining a distance allowing him to observe and represent details of appearance scrupulously, Eng Teng also infuses the image with warmth and gentleness. Portrait Head of Mother imparts a contained, reflective presence.

The importance of the human figure in Eng Teng's thoughts and art is not in dispute, and it will be discussed shortly; from the onset and throughout the advancement of his sculptural practice until the present, the figure constitutes a primary theme. Although it is pre-eminent, it is not an exclusive preoccupation. He leaves the figure and develops forms that are invented; he creates hybrid configurations by fusing components derived from human, geometric and organic sources.

These imaginary formations extend the field of iconography in the practice of sculpture in Singapore; in this connection Eng Teng has, more than any other sculptor, widened the scope of formal invention and symbolic expression. The variety of shapes and forms that he has created is unrivalled; the symbolic dimensions he develops are unmatched in complexity. The term iconography needs a little explanation as it may lead one to expect the demonstration of shared symbolic worlds through the dramatisation of myths and legends and the declaration of religious beliefs. For the most part the iconography in Eng Teng's sculpted world is privately determined. In this sense, iconography does not imply schemes or programmes prescribed by authority or any empowered agency; it is to be understood as a vital area or domain of creative invention, whereby new entities are produced which convey new meanings. As these originate front the imagination and personal vision of the artist, they can be grasped only with considerable effort and indirectly or intuitively.

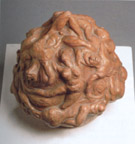

Responsibility I, c. 1960 (Fig. 96) and Squeeze (Fig. 97) are symptoms of these aims; they are exploratory, and approached in this spirit are seen as provocative and challenging. Conceptually and formally they breach the boundaries of sculptural thinking and making, assuming considerable liberties in the degrees to which representationality is transformed and almost abandoned. In these respects they mark milestones which remained unappreciated and, in all probability, incomprehensible at the time of their production.

Responsibility I, c. 1960 (Fig. 96) and Squeeze (Fig. 97) are symptoms of these aims; they are exploratory, and approached in this spirit are seen as provocative and challenging. Conceptually and formally they breach the boundaries of sculptural thinking and making, assuming considerable liberties in the degrees to which representationality is transformed and almost abandoned. In these respects they mark milestones which remained unappreciated and, in all probability, incomprehensible at the time of their production.

The first and immediate impact is the audacious treatment of the material; ciment fondu is pressed into assuming fluid characteristics as it is made to twist and turn, expand and contract, responding to the demands of the manipulating hands without resistance, and pliantly. Rarely, if ever, does Eng Teng employ this material with such abandon, yielding to intense improvisational approaches. And the outcome is compelling. In Responsibility I, the composition commences with an irregular cylindrical form whose surface is coiled; the threads of the coil are uneven as the raised body is irregular. As the cylinder ascends, it expands outwards into a writhing, amorphous mass which is crowned by a miniature head, whose features are abbreviated.

The first and immediate impact is the audacious treatment of the material; ciment fondu is pressed into assuming fluid characteristics as it is made to twist and turn, expand and contract, responding to the demands of the manipulating hands without resistance, and pliantly. Rarely, if ever, does Eng Teng employ this material with such abandon, yielding to intense improvisational approaches. And the outcome is compelling. In Responsibility I, the composition commences with an irregular cylindrical form whose surface is coiled; the threads of the coil are uneven as the raised body is irregular. As the cylinder ascends, it expands outwards into a writhing, amorphous mass which is crowned by a miniature head, whose features are abbreviated.

This is a dynamic composition, although it is not consistent; in it there are passages which are cluttered. The lower component can be interpreted as a spiral, a universal device denoting unending motion, having neither beginning nor ending. As it ascends the spiral expands; its material dimensions come into view forcefully. The velocity of movement affects the material body, pulling and pushing it from all directions, thereby deforming it. In the midst of this maelstrom there appears an element which acts as a steadying, calming centre; the head is the axis of the entire configuration and it manages to signal an alert, commanding presence. Taking the cue from the title, responsibility can be understood as an unending, gargantuan obligation which knows no bounds; yet, to fulfill it, a semblance of proportion or scale has to be gained, and for this detachment has to be exercised.

Squeeze shares compositional features with Responsibility I; contrasted with the compact, although volatile mass surmounting the coiled cylinder in the latter, in Squeeze the culminating component is highly articulated. The spiralling movement threatens to disintegrate the material body as tongue-like elements flick out into space and are ceaselessly undulating; some of them curl back on themselves while others remain extended and tremble as a consequence. The notion of sculpture as a stable, neatly contoured monolithic entity is considerably altered; instead of connected surfaces that define and secure three-dimensional properties, this work is enlivened by disjointed, erratic formal units which destabilise the environment. The environment is agitated as it responds to the pulls and pushes of the elastic formation; space no longer can envelop the form as a neatly-fitting glove but lodges in irregular recesses, curves around quirky shapes and quivers along ill-defined paths. The imagery evokes a sense of matter settling and assuming semblance of form by chance, and momentarily.

The formal constitution of these two works are undoubtedly unique; but they are not singular. For instance in Tragedy of War II, 1967 (Fig. 98) a similar combination of vertical and rounded elements are employed to describe the cloud formation ensuing from the detonation of a nuclear bomb. At first viewing, the image appears as a literal illustration of the famed mushroom-cloud shape publicised in the mass media and popular films. It is that and a little more. Closer inspection reveals tiny formations or rather deformations that appear creature-like, writhing in agony. The dome-like formation whose surface is intricately articulated, and seen to be supporting slithering life-forms, can be cited as an originating source for compositions featuring figures clinging to spherical forms that are placed on the floor and allowed to rock and swivel.

The formal constitution of these two works are undoubtedly unique; but they are not singular. For instance in Tragedy of War II, 1967 (Fig. 98) a similar combination of vertical and rounded elements are employed to describe the cloud formation ensuing from the detonation of a nuclear bomb. At first viewing, the image appears as a literal illustration of the famed mushroom-cloud shape publicised in the mass media and popular films. It is that and a little more. Closer inspection reveals tiny formations or rather deformations that appear creature-like, writhing in agony. The dome-like formation whose surface is intricately articulated, and seen to be supporting slithering life-forms, can be cited as an originating source for compositions featuring figures clinging to spherical forms that are placed on the floor and allowed to rock and swivel.

Earlier, mention was made of the human figure and its importance was underlined. An overview of this collection, including paintings and drawings, will reinforce its prominence. In his sculptural work, the figure enables Eng Teng to demonstrate his involvements with a wide range of social and political issues; the figure is also a vivid, palpable means to embody different emotional, psychological states or situations. From this, it maybe gathered that the approach to the figure is varied; and this is the case. There are compositions in which the figure asserts its pressure and appearance overtly; in them Eng Teng displays his knowledge of the conventions of modern sculpture as a tradition, both at the conceptual and formal levels; there are compositions in which the figure is subjected to radical mutations and, subsequently, new figurations emerge. Often these feature arrangements in which parts of the anatomy are abbreviated or omitted, while other parts are amplified; at times the figurations are made up by recombining anatomical parts, imbuing them with unaccustomed functions and in these ways they assume surprising, witty, even ominous presences. In the context of figurative sculpture in Singapore, Eng Teng has inaugurated an entirely novel domain of iconography; not surprisingly writers are corralled by the magnetism of these creations, and devote their commentaries to explicating their form and meaning.

Thy Name is Woman I and II, c. 1967 (Figs. 99, 100) can be seen as works dealing with woman in primordial states of being. In the world as defined by logos, being is revealed by the word and specified by the act of naming; hence the title - Thy Name is Woman. In the world made manifest by mythos, being is made palpable and visible by, amongst other means, the fabrication or formation of material, In Thy Name is Woman I, the figure is stirring from an inert state to an active one; the right leg is flexed while the left is slightly bent, giving rise to movements that animate the rest of the figure.

Thy Name is Woman I and II, c. 1967 (Figs. 99, 100) can be seen as works dealing with woman in primordial states of being. In the world as defined by logos, being is revealed by the word and specified by the act of naming; hence the title - Thy Name is Woman. In the world made manifest by mythos, being is made palpable and visible by, amongst other means, the fabrication or formation of material, In Thy Name is Woman I, the figure is stirring from an inert state to an active one; the right leg is flexed while the left is slightly bent, giving rise to movements that animate the rest of the figure.

Relief sculpture (as is this composition) is a dominant method of execution in sculpture; there are various kinds, and they all are attached to or set against a background support, the most prevalent being walls of buildings or architectural structures. Modern sculptors produce reliefs that are portable like paintings; and like paintings, they have no specific relationship to the places where they happen to hang. The primary appreciation of relief in sculpture stems from encountering a design or composition that is projected from a flat surface (ground) into a limited depth of space; such a design remains attached to the Surface. The depth of projection determines the height or shallowness of the forms, leading to the general distinction between high and low relief. This account may prompt connecting painting and relief sculpture for the reason that both deal with the relationship of figures to flat grounds; this connection can be Pursued only with the understanding that in relief sculpture, the projection of figures from the surface into depth in space is actual, whereas in painting it is illusory.

Relief sculpture (as is this composition) is a dominant method of execution in sculpture; there are various kinds, and they all are attached to or set against a background support, the most prevalent being walls of buildings or architectural structures. Modern sculptors produce reliefs that are portable like paintings; and like paintings, they have no specific relationship to the places where they happen to hang. The primary appreciation of relief in sculpture stems from encountering a design or composition that is projected from a flat surface (ground) into a limited depth of space; such a design remains attached to the Surface. The depth of projection determines the height or shallowness of the forms, leading to the general distinction between high and low relief. This account may prompt connecting painting and relief sculpture for the reason that both deal with the relationship of figures to flat grounds; this connection can be Pursued only with the understanding that in relief sculpture, the projection of figures from the surface into depth in space is actual, whereas in painting it is illusory.

Thy Name is Woman I is carved in low relief. While the head, torso and limbs are presented with conviction, the rendering of the upraised right arm is reduced to a generalised formal unit with unclear functions. The surface is marked by raised and sunken lines; these are grouped to generate varied rhythms simulating an agitated ground. The stirring of the figure, shifting away from a dormant state to a wakeful, assertive being is captured in some detail, The surface around the head supports a varied cluster of marks, corresponding to ripples generated by the movement of the head and arms; the figure emerges from an embryonic ground.

In Thy Name is Woman II the figure is seated; while the torso, upper and most of the lower limbs are in low relief, the head and right foot are in high relief. So much so that they extend beyond the perimeter of the relief surface and into actual space. This is a dramatic device employed to register the degree to which the figure is asserting a presence in space and, therefore, the extent to which it is consolidating a sense of being. The left arm is barely perceptible as it is largely enmeshed in the ground; the relief notation is gradually raised in the formation of the thigh, It is raised even further and expanded as the breasts, abdomen and right thigh come into view. In scanning this sector, the appreciation of surface and depth relationship defining the inner full and outer adjacent void volumes is enriched; these attributes lie at the root of sculptural thinking and, not surprisingly, are of crucial importance for Eng Teng in advancing his practice.

Thy Name is Woman I is presented for viewing as a picture; the other appears as a niche in a wall. The presentation strategies conform to the way relief compositions are to be seen and interpreted. In Thy Name is Woman II, Eng Teng breaches the function of the frame as marking the boundary of the composition; in extending the head and right foot into actual space, the image is linked to the environment directly, palpably, By making the connection tangible, the art work is inserted into common or shared space, appearing among other objects and entities, although retaining its distinctiveness. The implications surfacing from schemes such as these are germane to understanding the aims of presentation developed by Eng Tong.

Although produced two years later, Maxi, 1969 (Fig. 101) can be regarded as generically linked to the nude female figures in Thy Name is Woman I and II. As in the earlier compositions, Eng Teng sets aside the canons of proportion in order to heighten expressivity and dramatise viewing. In Maxi the head and upper limbs are reduced in size while the abdomen and upper thighs are amplified; these very same characteristics are visible in the earlier works. Maxi represents the setting free of the figure and it is seen striding in space, away from any attachment or encumbrance. And it is precisely to convey this sensation of walking, of walking with a mighty purpose and effect that proportions have been altered; in settling on a set of relationships, Eng Teng has turned to Giacometti and adopted that artist's scheme to suit his ends. If the image is positioned at a height above vertical eye-level, then it will loom into view in elevated space; seen at this height, the thighs bearing the weight of the body in motion will need sufficiently amplified mass in order to meet with the required function. In extending the viewing upwards, the abdomen appeals as a volume corresponding to that of the thighs. The movement tapers, curving up the s1ender arms and settling on the diminutive head which marks the conclusion of the visual trajectory.

Although produced two years later, Maxi, 1969 (Fig. 101) can be regarded as generically linked to the nude female figures in Thy Name is Woman I and II. As in the earlier compositions, Eng Teng sets aside the canons of proportion in order to heighten expressivity and dramatise viewing. In Maxi the head and upper limbs are reduced in size while the abdomen and upper thighs are amplified; these very same characteristics are visible in the earlier works. Maxi represents the setting free of the figure and it is seen striding in space, away from any attachment or encumbrance. And it is precisely to convey this sensation of walking, of walking with a mighty purpose and effect that proportions have been altered; in settling on a set of relationships, Eng Teng has turned to Giacometti and adopted that artist's scheme to suit his ends. If the image is positioned at a height above vertical eye-level, then it will loom into view in elevated space; seen at this height, the thighs bearing the weight of the body in motion will need sufficiently amplified mass in order to meet with the required function. In extending the viewing upwards, the abdomen appeals as a volume corresponding to that of the thighs. The movement tapers, curving up the s1ender arms and settling on the diminutive head which marks the conclusion of the visual trajectory.

The figure in motion is of perennial interest in sculpture; in the modern era Rodin revitalised this interest with fresh objectives, articulation and meaning. For instance, he dramatised walking and in Walking Man (1872) he propelled the figure - specifically the nude - into attaining new, powerful formal and iconographic presence. This production provoked a variety of responses; in the context of twentieth-century sculpture DuchampVillon's Torso of a Young Man (1910), Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) and Giacometti's City Square (1948-49) amongst others, constitute a pantheon of exemplary works. They vividly demonstrate the capacity of the human figure to continue to exemplify active states, symbolising differing physical, psychological and formal ideologies. Works such as these valorise the language of modern sculpture, and are available to artists practicing in diverse circumstances, globally. And Eng Teng's composition can be connected to this lineage as well. Even as it can, the occurrence which prompted its creation is particular. The mini-skirt was the most revolutionary garment in post Second World War fashion; it coincided with the emergence of youth in the forefront of popular culture and with various strategies mounted to free women from traditional roles and modes of behaviour. With its appearance, lithe and slim physiques were declared as the new ideals for physical beauty; those who did not naturally fit into this ideal set about subjecting themselves into conforming to it. In reaction to the mini, there appeared the maxi celebrating amplitude, encircling the figure with space and camouflaging its lineaments. These contending fashion statements characterised the 1960s in Singapore as well; the media was instrumental in propagating these competing ideals which were patronised by the youth. Maxi was prompted by considerations along these lines.

Modern sculptors generally turn away from genre for content in their art; indeed, as a category genre is identified and formulated to deal with painting. Sculptors avoid depiction of scenes and events from daily life partly because of the prospect of having to deal with narrative implications requiring either relief compositions or the staging of tableaux. In part, genre was bypassed because of anxieties emanating from creeping sentimentality leading to works condemned for being too literary, for illustrating the experience of others. Even as sculptors are insistent on being in this world, of delving into life's experiences for fuelling thoughts and sensibilities, they are equally insistent on the pre-eminence of expression and the expressive. The focus is not so much on actions and feeling of the subject but those of the sculptor and on the dynamics of form-making. Yes, there is interest in the body in movement in space; yet, the body is not necessarily an embodiment of particular identities. On the contrary, the drama of the body is the drama of sculptural form. It is in this sense that Maxi, while initially prompted by Eng Teng's encounter with the subjection of the body to the dictates of fashion, is transformed into an exposition of sculptural properties. Hence, the focus is on defining inner and outer volumes, and on articulating surface and depth relationships, And the endeavour is no less deserving of attention and esteem for prospecting these formal features. Maxi has been wrested from the strains of the everyday world and formed to appeal to quiet, intimate, aesthetic contemplation. Liu Kang, in responding to the works on display in the 1970 exposition concludes that Eng Teng's principal intention is to "explore the rhythms of pure lines, contrasts between solid and void, interplay of three-dimensional forms, forthright versus accommodating nature of shapes." These are the core preoccupations of modern sculpture.

Notwithstanding the tendencies outlined above, a handful of works in this collection can be regarded as conforming to the genre category; among these To Market, 1967 (Fig. 102) and Do We Look Down?, 1968 (Fig. 104) overtly exemplify rooting in this category. To Market, which is accompanied by a study (Fig. 103), is affiliated to subject matter in drawings and paintings produced between 1960-61. In them Eng Teng devoted considerable attention to depicting scenes of markets and of figures preparing fish, vegetables and rice.

Notwithstanding the tendencies outlined above, a handful of works in this collection can be regarded as conforming to the genre category; among these To Market, 1967 (Fig. 102) and Do We Look Down?, 1968 (Fig. 104) overtly exemplify rooting in this category. To Market, which is accompanied by a study (Fig. 103), is affiliated to subject matter in drawings and paintings produced between 1960-61. In them Eng Teng devoted considerable attention to depicting scenes of markets and of figures preparing fish, vegetables and rice. In still life compositions, the kitchen table appears replete with a similar range of edibles. Eng Teng has transferred subject matter developed for his pictures to his sculptural practice; in doing so, tensions arise in relating formal values with actions and feelings of the subject. The drawing shows an image which is settled in all particulars; the posture, the dominant shapes and details of attire, facial features and physiognomy are crystallised. Parallel lines are employed to contour voluminous forms which will ensue in converting the drawing into a three-dimensional design; in this matter, the transfer is effortless, requiring little or no change and modification.

In still life compositions, the kitchen table appears replete with a similar range of edibles. Eng Teng has transferred subject matter developed for his pictures to his sculptural practice; in doing so, tensions arise in relating formal values with actions and feelings of the subject. The drawing shows an image which is settled in all particulars; the posture, the dominant shapes and details of attire, facial features and physiognomy are crystallised. Parallel lines are employed to contour voluminous forms which will ensue in converting the drawing into a three-dimensional design; in this matter, the transfer is effortless, requiring little or no change and modification.

In the sculpted image the weight on the head is considerable and the outcome of the pressure is depicted in detail. The subject grimaces; the face is wreathed with lines of strain and the effort of the work. The neck muscles protrude in response to the strenuous effort; the arms are spindly, yet firmly hold the filled sack in place. These details, which vividly display the physical reactions of the subject, are confined to the upper portion of the body; from the torso down the interests change completely. The lower limbs are transformed into a cylindrical shape, amplified with an expansive inner volume. The surface of this section is articulated with raised lines, forming intricate geometric and floral patterns. Eng Teng has shifted his attention away from dealing with the effects of physical labour to converting the drapery of the figure into assuming complex formal sculptural considerations and decorative schemes.

Do We Look Down? does not betray any competing involvements; on the contrary, it is brutally forthright and uncompromising in describing the debilitating consequences of poverty. It is a relief composition featuring two figures severely foreshortened and presented looking upwards towards the viewer, between them is placed a begging bowl. The surface around them is marked with clusters of lines and nodules, appearing far more agitated when compared with the eddying areas surrounding Thy Name is Woman I. Eng Teng displayed this work in his first solo exhibition in 1970 and again in 1976; it did not receive any notice or mention at the time of its initial showing; in 1976, however, it drew attention and the composition was described at length. Referring to it as "expressionistic" and "Powerful" Tow Theow-Huang provides a succinct yet vivid account:

Do We Look Down? is a 1968 ciment fondu plaque installed at knee level so that we actually took down at rough and vigorously laid-down forms that project slightly from the rectangular surface. The figures are depicted in sharp "fore-shortening", so that the heads and arms seem disproportionately larger than the torsos and legs and the figures appear to peer up from a pit.

The centre of interest is a begging bowl, held by one of the figures and the emotive symbolism as well as the strong contrast between round bowl and rectangular plaque, create a powerful effect.

Tow Theow-Huang, 'Sculptures that rock and roll' in New Nation, November 26, 1976.

Earlier, mention was made of the anxieties attending the treatment of genre subjects b) modern sculptors, especially as it may lead to the ensuing works castigated for being sentimental and illustrative. Do We Look Down? veers close to that level, brushing along the alleyways of bathos. Eng Teng has devoted extensive resources in registering realism in the countenance of the figures; yet, the presentation does not point to fresh consideration of the relationship between poverty and the patronising attitudes adopted by those seeking to alleviate it. Indeed, it underscores the status quo.

Declining Man, 1969 (Fig. 105) is one of the earliest sculptural representations of a figure in distress in this collection. An elderly male figure is presented in the nude, reclining and turned on its left side. The face is gaunt and grizzled; the body is deformed with bones knobbled, protruding and the abdomen is distended. The figure is irredeemably alone and stripped of all signs of accommodation; yet, it emits a restrained presence. This is far removed from the rhetorically surcharged atmosphere in which Do We Look Down? is posed, Declining Man is laid out on its own ground, preoccupied in its own condition and being. There is not any perceptible moral or emotional gloss overlaid. The figure is composed and articulated vigorously; patterns of rhythm emerge from relating volume with volume and with adjacent planes. For instance, the spherical form of the head corresponds with the swollen abdomen and with the curvaceous planes of the knees. The deep-set eyes draw in dark pools of shadow as does the sharply curving chest and the complex interlocking ankles. Contours are robust and varied as they enclose and define interlocking components of the wiry anatomy.

Declining Man, 1969 (Fig. 105) is one of the earliest sculptural representations of a figure in distress in this collection. An elderly male figure is presented in the nude, reclining and turned on its left side. The face is gaunt and grizzled; the body is deformed with bones knobbled, protruding and the abdomen is distended. The figure is irredeemably alone and stripped of all signs of accommodation; yet, it emits a restrained presence. This is far removed from the rhetorically surcharged atmosphere in which Do We Look Down? is posed, Declining Man is laid out on its own ground, preoccupied in its own condition and being. There is not any perceptible moral or emotional gloss overlaid. The figure is composed and articulated vigorously; patterns of rhythm emerge from relating volume with volume and with adjacent planes. For instance, the spherical form of the head corresponds with the swollen abdomen and with the curvaceous planes of the knees. The deep-set eyes draw in dark pools of shadow as does the sharply curving chest and the complex interlocking ankles. Contours are robust and varied as they enclose and define interlocking components of the wiry anatomy.

Declining Man emerged from figurative compositions developed by Eng Teng during his pupilage at Farnham School of Art (1963-64); it will be recalled that while in that institution he recommenced drawing, especially drawing the nude figure; even though his principal engagement was with studio pottery, he was also interested in expanding the foundations of his sculptural practice. Occasionally, his studies of the nude figure were transferred from the drawing surface to three-dimensional compositions. A male figure, bound hand and foot, reclining on its left side was produced while studying in Farnham; it can confidently be claimed as a precedent for Declining Man. The kinship is apparent, visible, in similarity in posture and articulation of the body ' there are differences as well, springing chiefly from iconographic destinations. The bound figure highlights a male youth, athletic, which is fettered and encumbered; it is the nucleus for subsequent figurations symbolising captivity and bondage. Declining Man on the other hand, while it also features a male figure, deals with ageing and destitution; it is also preceded by a maquette (Fig. 107). Modelled in clay, it displays the design at an initial stage and tentatively; the proportion and positioning of the lower limbs are awkward, while the left arm appears as an undistinguished lump. These gain resolution, definition and function in the final composition. Declining Man has been realised methodically and vitalised by reprising an earlier composition.