![]()

![]()

[ All images © Chapungu Sculpture Park, harare, and may be used freely for any educational or scholarly purpose. All other uses require prior written permission.]

The sculpture of contemporary Zimbabwe, which has achieved such reknown in Europe, America, and Australia, has four sources or roots:

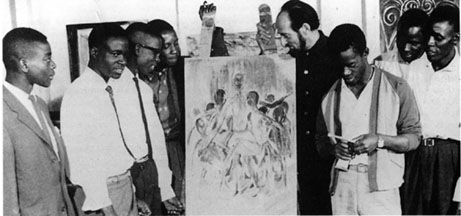

Frank McEwen in 1960 with founder members of the Woekshop School. A this point painting, rather than sculpture, predominates.

Frank McEwen in 1960 with founder members of the Woekshop School. A this point painting, rather than sculpture, predominates.

Frank McEwen (1908-1994), who had been hired by the Rhodesian authorities to introduce European high art into the National Gallery of Rhodesia, seems to have been a subversive force from the very beginning, since he seems to have been determined from his arrival to develop and then popularize the art of the country's indigenous peoples. According to Joceline Mawdsley, "he quietly began encouraging local people to try their hand at art -- initially, it would appear, in media with which they were familiar (ceramics, basketwork and weaving)," but he also introduced European painting on canvas. Mawdsley's discussions with the pioneering sculptures suggest that he increasingly turned to promoting "sculpture after seeing early work by men as Joram Mariga who, at that time had broken away from the use of soft stones and was experimenting with harder materials and more individualistic expression and themes." When McEwen arrived people were already producing

stone work for sale to tourists -- realistic interpretations of the wildlife, in the main produced in soft soapstone. Concurrent with the arrival of McEwen to the country's new National Gallery, it seems that a handful of carvers were independently breaking away from the established forms of carving and experimenting on their own. This new work seems to have ignited McEwen's enthusiasm and imagination and led to his assuming the role of encourager and 'director". Such artists initially brought their work to the National Gallery for selection and sale and McEwen, as often, would visit their 'studios' to guide, comment and initiate he relationships from which the movement was to be born.

McEwen provided materials, a place to work, criticism, and tireless advocacy culminating in a series of local and international exhibitions, the first and perhaps most important of which was the 1971 show at the Musée Rodin, Paris. "Other important exhibitions were to follow, chiefly Shona Sculptures of Rhodesia held in 1972 at the I.C.A. Gallery, London and a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, also in 1972. These received tremendous critical acclaim and marked the beginning of acknowledgement of the sculpture." Worried that commercial success might corrupt the new afrt form in its early stages, " he enlisted the help of sculptor, Sylvester Mubayi in establishing a rural community in the powerful environment of the Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe - the Nyanga district - and named it Vukutu."

One is perhaps not surprised to discover that McEwen, a European art expert friendly with major figures of contemporary European art, should have so eagerly supported work by indigenous artists once he encountered them. Tom Blomefield is another matter. As Mawdsley relates this fascinating story, he founded "a quite separate and different community of sculptors, . . . in the late sixties in the North East" part of the country:

Blomefield had been a tobacco farmer in Guruve who, through the pressures of international sanctions after Ian Smith's Declaration of Unilateral Independence (UDI), was no longer able to provide reliable employment for his farm workers - many of whom had travelled to Zimbabwe from Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Angola. In an effort to continue his support for these men and their families he encouraged them to make the change from farm labouring to art. The land on which the community was sited included an impressive natural deposit of hard, carveable Serpentine and it was to be stone carving for which his men became respected and applauded over the following twenty years. Frank McEwen and the National Gallery supported this community for several years, before the establishment of its own rural Workshop at Vukutu. Tengenenge then continued on its own path and still thrives today. . . . With no artistic training and very little knowledge of the arts, Blomefield nevertheless felt passionately about the natural creative potential within the African people in Zimbabwe. Within an unshakeable (some would say naive) belief in the ability to live by simple means and personal resources in times of hardship, he displayed immense courage in implementing his ambitions.

The period of the War of Liberation in the '70s proved a very difficult time for many sculptors, some of whom stopped working during these years. Mawdsley explains that "during the war years it was almost impossible to exhibit or sell work and individuals such as Roy Guthrie could only encourage and financially support the artists by purchasing works for the future exposure they believed possible in more peaceful times." After independence, when the trade embargo lifted, Guthrie organized international exhibtions and continued to maintain Chapungu, which contains the largest permanent reference collection of the major sculptors.

Arnold, Marion: Zimbabwe Stone Sculpture, Louis Bolze, Bulawayo,1986.

Kuhn, Joy: Myth and Magic - The Art of the Shona of Zimbabwe, Don Nelson, Cape Town,1978.

Mawdsley, Joceline. Chapungu: The Stone Sculptures of Zimbabwe. Harare: Chapungu, 1997.

Sultan, Oliver . Life in Stone: Zimbabwean Sculpture -- Birth of a Contemporary Art Form. Revised Edition. Harare: Baobab Press, 1994.

Winter-Irving, Celia: Stone Sculpture in Zimbabwe: Context, Content and Form, Roblaw Publishers, Harare, 1991.