![]()

![]()

[ The following essay has been adapted with the kind permssion of the Director, Chapungu Sculpture Park, from Chapungu: The Stone Sculptures of Zimbabwe (1995). All images © Chapungu Sculpture Park, Harare.]

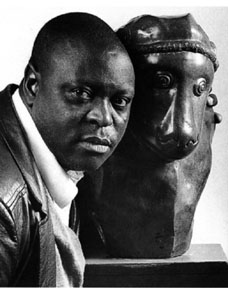

John Takawira dominated the Zimbabwean sculpture scene for much of him career. His untimely death in 1989, at the age of 50 left a void still sorely felt today. Born in 1938 in Chegutu, he grew up in Nyanga. Like his brother Bernard, he was greatly influenced by his mother and perhaps more than any of the sons, retained his traditional upbringing and beliefs and portrayed them endlessly in his sculpture.

John Takawira dominated the Zimbabwean sculpture scene for much of him career. His untimely death in 1989, at the age of 50 left a void still sorely felt today. Born in 1938 in Chegutu, he grew up in Nyanga. Like his brother Bernard, he was greatly influenced by his mother and perhaps more than any of the sons, retained his traditional upbringing and beliefs and portrayed them endlessly in his sculpture.

He was led to sculpture by his uncle, Joram Mariga, at the age of twenty. Frank McEwen noticed his remarkable talent immediately and he became one of the first members of the Workshop School, with his work being exhibited in the National Gallery from 1963. When, in 1969, Frank McEwen moved the school to Vukutu, John was to be one of the most important figures within its small community and in such powerfully spiritual surroundings his work found freedom. Here he was able to lead a simple and purposeful life and his sculpture could develop, free from the pressures of commercialism and unnecessary interruptions. Images such as his skeletal figures and baboon/ man creatures took precedence and came alive. In 1971 Frank McEwen organised a highly significant exhibition at the Musée Rodin in Paris. Here, Takawira's Skeletal Baboon was exhibited and McEwen was to say later, "his vibrant Skeletal Baboon, with its almost pleasant grin, was considered by Charles Ratton, perhaps one of the greatest experts on African art forms, to be the best art to come out of Africa in this century." It was this exhibition which set his career in an international context.

His uncompromising nature ensured that his development continued apace, producing ever more startling and innovative work. He was one of the first sculptors, for example, to experiment with the surface of the stone; combining polished areas with the unkept, but powerful natural rough skin, or leaving evidence of his working methods in the marks etched onto the stone in moments of hurried insight. Continually exploring spiritual and personal depths, his sculpture used powerful combinations of forms and, often carving right through the stone, holes and voids played a crucial part in the overall image, representing the all-seeing spiritual 'eye' of the piece. Willowy and fragile in appearance, his smaller works embodied enormous spiritual superiority and strength. Water Spirit (1983) is a fine example, with its uneven, liquid surface and forlorn expression. There is little imposition on the part of the artist and the viewer could be forgiven for thinking his role was purely to assist in the emergence of the spirit. Women play a very visible role in his work - with elongated necks and flowing hair, they look down on the viewer with a detached power. Many seem to have closed eyes as if in contemplation or pain, but the vital role which John so obviously saw for them is clear. They embody the strong, creative and empowering personality so inspirational in his own mother.

Working in the hardest, darkest Springstone, Takawrira sought always to be individual and different from those around him. At times a difficult personality, he was nevertheless uncompromising to the end - traits that are perhaps typical in a leader (of international stature) within his own field. John Takawira won awards in the National Gallery Heritage exhibitions on many occasions and has more work in the Permanent Collection of the National Gallery than any other artist.

Mawdsley, Joceline. Chapungu: The Stone Sculptures of Zimbabwe. Harare: Chapungu, 1997.