PIONEER architect Tay Kheng Soon has once again spoken out strongly about architecture in Singapore.

The last time the 61-year-old took a stand, it was about the demolition of the National Library in Bras Basah. He was opposed to its demolition but could not argue for its preservation.

He has now made a cause celebre of the design of the new Supreme Court complex in the former Colombo Court site.

His sentiments, published in a Forum letter in The Straits Times on April 25, could not be less emphatic. He wrote: 'I was appalled by the design.'

PWD Consultants is the project coordinator behind the new Supreme Court complex, which is scheduled to be completed in 2004. British design consultancy, Foster and Partners, was selected from a shortlist of 13 international architectural firms drawn up by PWD Consultants.

The design of public buildings often becomes controversial as members of the public feel they have a right to be consulted. But design is not an easy entity to qualify and exactly who should be held accountable is even less clear.

One of Tay's major grievances is that being a potentially important civic building, the public should have been allowed to give its feedback at the onset of the design, and not after the design had been approved for construction.

Apart from obtaining government approval, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), the nation's planning authority, does not actually require that the Supreme Court make the design public.

However, the URA did have certain safeguards against 'appalling' designs in the civic district. But its design advisory panel, the now-defunct Architectural Design Panel (ADP), was dissolved in 2000.

A URA spokesman confirms that the design of the Supreme Court had not undergone the panel's scrutiny. He says: 'The ADP had been dissolved in 2000, before the Supreme Court was designed.'

The ADP has since been replaced by the Design Advisory Committee (DAC) and the International Panel of Architects and Urban Planners (IPAUP).

Like the ADP, the DAC and IPAUP provide design guidelines along major corridors, to ensure that new structures are sensitive to the existing context. But unlike the ADP, clearance from the DAC and IPAUP is no longer required on important buildings as a condition of URA's planning approval.

Speaking to an audience of architects in April 2000, Minister for National Development Mah Bow Tan, who announced the ADP's dissolution, said: 'With the maturing of our architectural profession and a better appreciation of the value of good design, there is a general consensus that the panel may no longer be necessary.'

Indeed, the URA's position is not to dictate design, and more bureaucracy is certainly not the answer either.

But the president of the Singapore Institute of Architects (SIA), Mr John Ting, thinks that consultations with relevant professional bodies are useful. The SIA is the only professional body recognised by the government which represents the architects and the profession. Tay was himself a former SIA president.

Of the controversy over the design of the new Supreme Court complex, Ting feels the SIA should have been consulted.

'The more learned among us should be party to the formulation process rather than be standing on the outside, reacting to the design,' he says.

But he acknowledges that a more comprehensive consultation process with the SIA could still have resulted in a design that is not so different from the final one.

He says: 'Yes, the building might be the same in the end, but at least they would have made the effort to inform the audience.'

BUT not all architects agree with him on the final design of the Supreme Court.

Tay is one of the more vocal exponents of the architecture scene, but his is by no means the only voice calling for a more considerate approach to civic planning.

Architect Tan Hock Beng gave Parkview Square, a building opposite Bugis Junction, the thumbs down.

In an interview with The Straits Times on Feb 4, he said: 'It seems too out of place and has bad elements of Las Vegas and Hollywood put together.'

The building, a 24-storey office block, is not a public one, so there was even less need to consult the public on the design.

But more serious, perhaps, are his views about public buildings like the 'aesthetically confused' The Esplanade - Theatres On The Bay.

He says: 'If you take the roof off, no one would be able to tell what the building is. The roof is just a little hood, multiplied a hundred times. The form has no sense of the activity, energy or jubilation it contains.'

THAT both The Esplanade and Parkview Square were designed by foreign architects is perhaps a particularly prickly thorn-in-the-side of many Singaporean firms.

Briton Michael Wilford was responsible for The Esplanade and American James Adam for Parkview Square. Both parties, however, collaborated with local firm, DP Architects.

It is not said explicitly, but many architects here feel developers still believe only a foreign architect can produce good work.

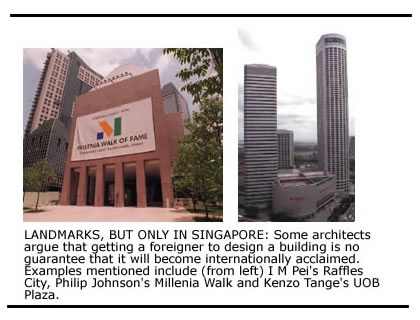

Architects like Tan argue that getting a foreigner is no guarantee of a good building, regardless of the firm's reputation.

He says that of the many big-name architects who have built in Singapore, like I M Pei, Kenzo Tange and Philip Johnson, 'not a single building designed by them for Singapore is internationally acclaimed'.

Tange designed the UOB Plaza and the Indoor Stadium; Pei was behind Raffles City while Johnson conceptualised Millenia Walk.

Is the problem of design in Singapore just a matter of transparency?

Tan thinks not.

'It's a question of the design brief. If you have a conventional brief, you can't expect spectacular architecture,' says Tan, pointing his finger at developers.

Robert Powell, a former lecturer at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, agrees that it is not simply a matter of whether an architect is local or foreign.

'We should not put the blame for mediocrity solely on foreign architects. Local architects, too, have produced much mediocrity. The Parliament House, which could have been a landmark for the nation, is a timid building with no presence.'

Like Tan, Powell also feels that the quality of architecture depends on the working relationship between the client, architect and building authorities.

'If there are too many compromises or any failure of nerve, the Supreme Court will end up like others, for example The Esplanade, a good rather than great building.'

But no matter who is assigned the blame, many still feel the architecture in Singapore is, at best, mediocre.

Having had a closer look at the model of the Supreme Court complex, Tay now feels that the design lacks an 'appropriate design symbolism'.

Left with no clue on how to understand and read the architecture, or how designs evolve, important landmarks are reduced quickly to the level of caricature.

The Esplanade, with its two distinctive parts, is already fast becoming referred to as the 'durian' or 'fly' building.

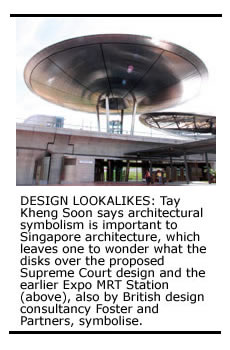

And in the case of the Supreme Court, some question why the same floating disk appears in the design of another local building - the Expo MRT station at the Singapore Expo in Changi, which was also designed by Foster and Partners.

Unfortunately, this is probably not a question that will be answered as the design for the building has already been approved and it is now waiting to be built.

BUT not all hope is lost. On April 30, over 200 competition entries for the design of the much-touted Duxton Plain public housing went on display at the URA Centre in Maxwell Road.

The event was publicised widely eight months ago, in Singapore and internationally, and drew contestants like internationally-acclaimed architects Tange, Zaha Hadid and Will Alsop.

It might not be the most important public building, but it will certainly be the biggest.

Tay himself took part in the competition. But the first prize went to ARC Studio, a very young and small Singapore firm.

With the competition, it seemed every possible measure was taken to ensure the best design was selected. This meant a judging panel that included several renowned architects. The competition was also the first for public housing in Singapore.

With so much effort made to get the perfect design for Duxton Plain, will Singapore get a good example of local architecture finally?

Tay, who was present at the exhibition, did not want to comment. It seems the public will have to decide.

Last Modified: 11 July, 2002