The Bali Field Trip, Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng

Kwok Kian Chow

This document is part of a joint project of the Singapore Art Museum and the Honours Core Curriculum, National University of Singapore. This image and accompanying text appears here with the kind permission of the Singapore Art Museum.

In 1952, Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng went on their historic field trip to Bali. While it would not be accurate to state that the Nanyang artists went to Bali because of Le Mayeur or even Gauguin's inspiration, Le Mayeur did create a deep impression of Bali in the Singapore art circle and, in fact, the artists met him during that trip.

The pioneers went to Bali mainly to search for a visual expression that was Southeast Asian. Not only did Bali offer them a rich visual source, the Balinese experience also revealed the ritualistic, experiential and decorative nature of Southeast Asian art -- a point which sets the Singapore story apart from the Gauguinian legend.

During and after the trip, images of Bali provided both the inspiration and visual sources which enabled the artists to crystalise their exploration of an aesthetic style in Singapore art. The artists were driven by two cross-currents - ore was the search for pictorial representation of the Naryang culture (i.e., the Nanyang School in art). The other was an advancement of the Symbolist value of the artist as a creative individual who is able to transform "primitive" art to formulate a new artistic language. This second notion was an aesthetic value and practice with roots in the West, but it found resonance in Singapore in the 1950s as artists were being recognised as individual talents by newly-formed institutions such as the British Council. This spurred much innovation in the visual arts and even Lim Hak Tai, the founder of NAFA, experimented with new pictorial idioms in the 1950s of which Composition of 1955 is an example. Cheong Soo Pieng was quoted in the mid-1950s on the significance of the Bali field trip:

(In painting I first) experimented a good deal in colour technique, and when I had evolved a technique which pleased me I tried it upon studies of the human form. I went to Bali on a sketching trip, and there I was fascinated by the scenery and by the Balinese women. I discovered that Balinese women are the ideal subject for me, and I made a good number of paintings, modern in feeling and to my own liking many of which I do not wish to sell. [v1, n2, pp. 27]

Cheong Soo Pieng received formal art education in China, and developed a distinctive style throughout his career in Singapore. Writings on Cheong's art are very much based on his formalistic development according to the following "phases of experimentation": oil in impasto effects (1948-59), Chinese ink on rice paper (1960-63), oil with new effects (1963-68), abstraction (1968-70), mixed media sculptures and porcelain work (1970-72), abstraction continued (1972-79), oil with new effects (1975-83), Chinese ink with new effects (1979), painting on tiles and porcelain (1982-83), and Chinese traditional medium on cotton (1983) (National Museum).

Cheong first studied art at Xiamen Academy of Art and subsequently enrolled at the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts in Shanghai. After arriving in Singapore in 1946, he lectured at the NAFA from 1947 to 1961. Indians and Cows, an oil painting of 1949 is representative of Cheong's work in the late-1940s. By the time Cheong came to settle in Singapore, he was already an accomplished artist, proficient with the methods and materials of ink painting. After his arrival, Cheong lost no time conceptualising and forging a new art form which he felt was more compatible to his newly-adopted tropical home. He sought to capture the colours and charms of local life in a whole new pictorial language. Indians and Cows reflects Cheong's eagerness to look at and adopt new motifs for his pictorial composition. A large tree trunk divides the painting boldly into two unequal parts -- the Indian herdsmen facing ore another in conversation at the edge is almost overwhelmed by the two resting cows at the centre of the picture. The palpable presence of the animals is heightened by the soft, sinuous outlining of their silhouettes and the sensitive modelling of their forms.

Cheong's innovative spirit drove him ceaselessly to test new ideas and explore new visions. Seaside, executed in 1951, was one such experiment. The motif of the sea is not obvious at first glance. Upon closer examination, the familiar elements of seascape such as boats and a fishing village are revealed. Seaside conveys a sinister mood, conjuring a haunting image of a dream world where reality and the imaginary meet and interact. It is an example of Cheong's remarkable ability to render and elevate the everyday and commonplace to the level of fantasy and the extraordinary. Cheong's continual investigation of the painted composition resulted in works such as Malay Woman, probably of the mid-1950s. Here, the atmospheric effect of the work is reduced with emphasis shifting to more pictorial and composition interests.

Cheong's innovative spirit drove him ceaselessly to test new ideas and explore new visions. Seaside, executed in 1951, was one such experiment. The motif of the sea is not obvious at first glance. Upon closer examination, the familiar elements of seascape such as boats and a fishing village are revealed. Seaside conveys a sinister mood, conjuring a haunting image of a dream world where reality and the imaginary meet and interact. It is an example of Cheong's remarkable ability to render and elevate the everyday and commonplace to the level of fantasy and the extraordinary. Cheong's continual investigation of the painted composition resulted in works such as Malay Woman, probably of the mid-1950s. Here, the atmospheric effect of the work is reduced with emphasis shifting to more pictorial and composition interests.

Dato Loke Wan Tho, reputedly the most ardent art patron from the mid-1950s, paid tribute to the distinctiveness of Cheong Soo Pieng's style:

Soo Pieng is, undoubtedly, the most versatile of the many gifted people who practise the graphic arts in this country He seems to be equally at home using oils, water-colours, chalk, and now, also the dyes and hot wax of the worker in batik. He is an artist who has many strings to his bow, or many brushes in his paintbox: thus, at one moment, he is Chung Say P'un, painting in the techniques which are traditional to the Chinese artist; but more often he is Soo Pieng Cheong, or Soo Pieng Cheong, or Soo Pieng Choong, or even S.P. Chong, a painter who is deeply influenced by the artists of the West -- Gauguin, Picasso, Modigliani, Vlaminck, Braque. But the important thing is that, no matter in what style he may choose to work, the personality of the lndivldual, Soo Pieng, is always there; so that if you walk into a room you are able to say at once, "that's a Soo Pieng." And what more can you ask, than that a man should be himself, even if he is lnfluenced by other artists? [Loke Wan Tho, speech, Oct 10, 1956]

Cheong's oils in impasto effects of the late-1950s moved toward greater fattening and schematising of composition. The figures in Bali Girls and Iban Girls are captured in single-colour patterns. In the early 1960s, Cheong was able to render his archetypal figures in Chinese ink, creating a softer effect by ink washes. He also applied traditional Chinese ink techniques to provide texture and for decoration, thus replacing the earlier heavy impasto patterns An example of Cheong's ink work in the 1960s is Drying Salted Fish.

Cheong's oils in impasto effects of the late-1950s moved toward greater fattening and schematising of composition. The figures in Bali Girls and Iban Girls are captured in single-colour patterns. In the early 1960s, Cheong was able to render his archetypal figures in Chinese ink, creating a softer effect by ink washes. He also applied traditional Chinese ink techniques to provide texture and for decoration, thus replacing the earlier heavy impasto patterns An example of Cheong's ink work in the 1960s is Drying Salted Fish.

Among the four pioneer artists that went to Bali, Chen Chong Swee best represents the realist end of the stylistic spectrum. He was also a prolific writer contributing articles to the press, exhibition catalogues, and magazines published by art associations and was one of the first Singapore artists to incorporate local scenery in ink painting. His conviction to realism was frequently expressed in his articles and colophons on paintings:

Art is a part of life and cannot exist independently from real life. Art must be objective. If it falls to be accepted by another person, it loses its essence of universality and can no longer exist as art. If a work of art fails to embody truth, goodness and beauty, it cannot be regarded as a true work of art. [Cited in Kwok Kian Chow pp. 10-11].

Chen graduated from Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts in 1931 and arrived in Singapore that same year. He was a teacher (as most artists were from the 1930s to about the 1970s and taught at Tao Nan, Tuan Mong, Chinese High and Chung Cheng High schools. Chen worked mainly in ink and watercolour although he also did some oils.

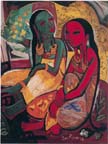

Balinese Women, an oil painting finished shortly after Chen's return from Bali, portrays two Balinese women going about their chores. The rendering of precise outlines and the clever use of colour enhance the realism of the two figures. The composition is well thought-out, the difference in scale of the figures giving an illusion of distance between them, lending spatial depth to the painting. The youthful body of the woman in the foreground exudes strength and vitality, qualities which are enhanced by her sunshine yellow headdress. Chen wrote: ".. . Bali is indeed a women's empire; the robust beauty of Balinese women and the pastoral scenery form an excellent painting" (Cited in Kwok Kian Chow p. 15). But he did not only see Balinese women as ideal models, he also had a high regard for them for their important social and economic roles.

Returning From the Sea was completed by Chen in 1972. The painting depicts fishermen returning to shore, busily winding up the day's activities, pushed along by a storm brewing in the distance. The turbulent sea is in shades of green, blue and gray with a tinge of white to suggest the rising foam as waves strike the shore. The use of flat-distance composition helps to give the painting an expansive view of the seascape and a sense of immediacy to the activity. A light, atmospheric quality is achieved via an effortless blend of colour tones and slight touch of brush -- a technique not unlike Chinese ink painting of which Chen was a master.

Returning From the Sea was completed by Chen in 1972. The painting depicts fishermen returning to shore, busily winding up the day's activities, pushed along by a storm brewing in the distance. The turbulent sea is in shades of green, blue and gray with a tinge of white to suggest the rising foam as waves strike the shore. The use of flat-distance composition helps to give the painting an expansive view of the seascape and a sense of immediacy to the activity. A light, atmospheric quality is achieved via an effortless blend of colour tones and slight touch of brush -- a technique not unlike Chinese ink painting of which Chen was a master.

If Chen Chong Swee represented the Realist end of the stylistic spectrum, Liu Kang was the Post-impressionist end.

Liu Kang graduated from the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts three years earlier than Chen Chong Swee. He continued his studies in Paris between 1928 and 1933 and was president of the Society of Chinese Artists from 1946 to 1958.

Autumn Colours, Farmer's House and Breakfast, works from Liu's Paris period in the early 1930s, show the influence of Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin in aspects of the Post-impressionist pictorial interests -- expressiveness of brush strokes, imposing presence of and flattening and merging of planes to construct colour blocks. Autumn Colours is a picture permeated with the warm glow of scattered greens, reds, yellows and browns, capturing the shimmering mood of autumn. Farmer's House moves towards the presentation of pictorial and composition interest in which the rambling structure of the house dominates the entire picture plane. Breakfast, painted in 1932, two years later than the other two works, manifests Fauvist sensitivity towards colour, form and design although the basic approach appears to be narrative: the laid out meal, the open book and the perspective which invites the participation of the viewer. The three works also show, in the order listed, a gradual thickening of outlines in defining object and spaces -- suggesting an affiliation with the linear brush quality of Chinese ink painting.

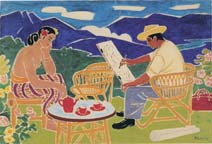

In Artist and Model which shows Chen Wen Hsi sketching a Balinese woman, Liu Kang's dark outlines have become white -- an innovation which could have been inspired by batik painting. Painted in 1954, this work may be based on a sketch made during the artists' field trip to Bali two years earlier. Chen is seated, working on a sketching board propped on another rattan chair. This rhythmic repetition of chairs, further echoed by the number and arrangement of tea pot and cups on the round table makes the entire painting delightfully casual and whimsical.

In Artist and Model which shows Chen Wen Hsi sketching a Balinese woman, Liu Kang's dark outlines have become white -- an innovation which could have been inspired by batik painting. Painted in 1954, this work may be based on a sketch made during the artists' field trip to Bali two years earlier. Chen is seated, working on a sketching board propped on another rattan chair. This rhythmic repetition of chairs, further echoed by the number and arrangement of tea pot and cups on the round table makes the entire painting delightfully casual and whimsical.

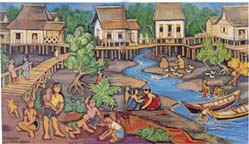

Life by the River, a 1975 work, shows a village scene with busy human activity. Liu Kang is a master of composition. Depth in this painting is achieved more by the arrangement of shapes than by perspective, suggesting a pictorial sensitivity more in tune with the Chinese landscape tradition. The yellow walkway on the left and the river on the right not only echo each other, but also lead the viewer's attention to the houses in the distance.

Life by the River, a 1975 work, shows a village scene with busy human activity. Liu Kang is a master of composition. Depth in this painting is achieved more by the arrangement of shapes than by perspective, suggesting a pictorial sensitivity more in tune with the Chinese landscape tradition. The yellow walkway on the left and the river on the right not only echo each other, but also lead the viewer's attention to the houses in the distance.

Like Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi favoured Post impressionism, but he was also an abstractionist, captivated by the colours, forms, movements and textures of Bali.

Chen Wen Hsi lived in Singapore from 1947. Chen, who studied at both the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts and Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1920s and early 1930s, met Chen Chong Swee and Liu Kang at Xinhua. Chen was enrolled in the art education department where both traditional ink and Western painting were taught. Travelling widely between Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Xingning and his home county of Jieyang in Guangdong during the 1930s and 1940s, Chen, then an art teacher, painted primarily in ink, his work imbued with a strong descriptive power and sentimental feeling (Kwok Kian Chow p. 6).

Hometown, a work of this period, shows a mother with her children grouped around her, The setting is of a traditional Chinese village with the figures gathered under a willow tree, its soft and gentle foliage enhancing the sentimental mood of homeliness. Chen's muted tones and simple lines make it easy for the viewer to empathize with this idyllic scene.

Hometown, a work of this period, shows a mother with her children grouped around her, The setting is of a traditional Chinese village with the figures gathered under a willow tree, its soft and gentle foliage enhancing the sentimental mood of homeliness. Chen's muted tones and simple lines make it easy for the viewer to empathize with this idyllic scene.

Chen Wen Hsi's appreciation of Western painting styles was based on the aesthetic value of the Chinese literati which regarded subjectivity as the highest form of expression. He regarded Impressionism as waiguan-pai (school of exterior appearance) and he appreciated Post-impressionism -- which emphasised brushwork (i.e., formal quality) -- as a further advancement towards subjective expression. Chen felt that he was more at home with Western modernist trends after the Post-impressionists (Kwok Kian Chow p. 7) and was therefore the least engaged in the discussion on the Nanyang School although the impact of the Bali field trip in 1952 on his art was no less than those of his three fellow travellers.

Grazing , a semi-abstract oil, is one of Chen Wen Hsi's forays into the medium. In this composition of a herd of grazing cattle, Chen was clearly experimenting with fragmented space, using only scale to indicate depth. Despite the discordant colours and chopped up space, Chen manages to establish a certain rhythm whlch would continue to be characteristic of his art. There is the same energy of repeated and jagged marks in his calligraphy and ink paintings.

Grazing , a semi-abstract oil, is one of Chen Wen Hsi's forays into the medium. In this composition of a herd of grazing cattle, Chen was clearly experimenting with fragmented space, using only scale to indicate depth. Despite the discordant colours and chopped up space, Chen manages to establish a certain rhythm whlch would continue to be characteristic of his art. There is the same energy of repeated and jagged marks in his calligraphy and ink paintings.

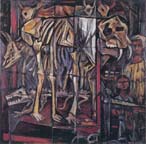

In the Museum is a fine example of Chen's concern for formal innovation in the 1950s. Painted in 1956, this work depicts a zoological exhibit in the National Museum when it was a natural history museum and known as Raffles Museum and Library. In a representation of multiple viewpoints in the Cubist idiom, Chen was as concerned with capturing the clinical anatomical details of the skeletons on display as he was with expressing the ambience of the gallery and the vision that arrested and engrossed visitors.

In the Museum is a fine example of Chen's concern for formal innovation in the 1950s. Painted in 1956, this work depicts a zoological exhibit in the National Museum when it was a natural history museum and known as Raffles Museum and Library. In a representation of multiple viewpoints in the Cubist idiom, Chen was as concerned with capturing the clinical anatomical details of the skeletons on display as he was with expressing the ambience of the gallery and the vision that arrested and engrossed visitors.

Loke Wan The accurately summed up Chen Wen Hsi's artistic direction in the 1950s when he opened Chen's exhibition in 1958:

Mr Wen-Hsi, of course, began his career in China, and so we would expect him to be influenced by the emphasis which that country's artists have always placed on nuance, and the swift, sure and sentient line. in this form of expression he is, of course, a master. But he is also able to peer through that window which opens onto the Western world, and with his imagination thereby enriched, he in turn enriches us with the product of his fancy (speech, Dec 23, 1958).

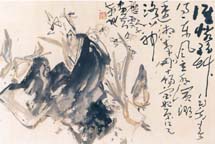

Narcissus and Sparrow in the Rice Field are excellent examples of Chen Wen Hsi's unique synthesis of expressive painting style and calligraphy. There is a harmonious blending of the written word with the delicate brushwork that describes the narcissus blooms and the deft brushstrokes that portray a lone sparrow perched on a fragile strand of grass, Herons, a work in his mature style of the 1980s, exemplifies Chen's radical approach to painting animals in Chinese inks. Here, the artist exhibits his confidence in abstraction. The interlocking herons exist in undefined space and the composition has become non- hierarchical with no exterior boundaries. With the interchangeability of solid and void, the depth also becomes an infinity. This perspective also allowed Chen to manifest his virtuosity in the Chinese brush technique in a bold new way.

Narcissus and Sparrow in the Rice Field are excellent examples of Chen Wen Hsi's unique synthesis of expressive painting style and calligraphy. There is a harmonious blending of the written word with the delicate brushwork that describes the narcissus blooms and the deft brushstrokes that portray a lone sparrow perched on a fragile strand of grass, Herons, a work in his mature style of the 1980s, exemplifies Chen's radical approach to painting animals in Chinese inks. Here, the artist exhibits his confidence in abstraction. The interlocking herons exist in undefined space and the composition has become non- hierarchical with no exterior boundaries. With the interchangeability of solid and void, the depth also becomes an infinity. This perspective also allowed Chen to manifest his virtuosity in the Chinese brush technique in a bold new way.

References

Cited in Kwok Kian Chow. "Chen Chong Swee: His Thoughts" in National Museum. Chen Chong Swee: His Thoughts, His Arts. Singapore, 1993.

Kwok Kian Chow. "A Dialogue with Tradition: Chen Wen Hsi's Art of the '80s" in catalogue for exhibition of the same title. Singapore: National Museum, 1992.

National Museum. Cheong Soo Pieng Retrospective. Exhibition catalogue 1991.

Singapore Art Society. "Cheong Soo Pieng" The Singapore Artist, 1954.

Last updated: May 2000

Cheong's innovative spirit drove him ceaselessly to test new ideas and explore new visions. Seaside, executed in 1951, was one such experiment. The motif of the sea is not obvious at first glance. Upon closer examination, the familiar elements of seascape such as boats and a fishing village are revealed. Seaside conveys a sinister mood, conjuring a haunting image of a dream world where reality and the imaginary meet and interact. It is an example of Cheong's remarkable ability to render and elevate the everyday and commonplace to the level of fantasy and the extraordinary. Cheong's continual investigation of the painted composition resulted in works such as Malay Woman, probably of the mid-1950s. Here, the atmospheric effect of the work is reduced with emphasis shifting to more pictorial and composition interests.

Cheong's innovative spirit drove him ceaselessly to test new ideas and explore new visions. Seaside, executed in 1951, was one such experiment. The motif of the sea is not obvious at first glance. Upon closer examination, the familiar elements of seascape such as boats and a fishing village are revealed. Seaside conveys a sinister mood, conjuring a haunting image of a dream world where reality and the imaginary meet and interact. It is an example of Cheong's remarkable ability to render and elevate the everyday and commonplace to the level of fantasy and the extraordinary. Cheong's continual investigation of the painted composition resulted in works such as Malay Woman, probably of the mid-1950s. Here, the atmospheric effect of the work is reduced with emphasis shifting to more pictorial and composition interests.