This document is part of a joint project of the Singapore Art Museum and the Honours Core Curriculum, National University of Singapore. This image and accompanying text appears here with the kind permission of the Singapore Art Museum.

While a healthy art market emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, the cross influence of Singapore's own tradition of realist art, earlier concerns for woodcut and caricature of social themes, and continued aesthetic exchange from China gave rise to a Social Realist trend.

Its roots can be traced to 1898 when Kang Youwei, the leader of the Chinese Reform Movement, had advocated the principle of "Western outer shell and Chinese inner kennel." Since then, the interpretation of this synthesis in the visual arts had been a problem that went through many different articulations. One high point was the famous debate, in 1929, between the Academic or Literal Realists represented by Xu Beihong and those supportive of newer Western trends (such as the Fauvist) represented by Xu Zhimo. The heightened political sentiment within the cultural circle in the course of events which led to the Second World War gave rise to a renewed emphasis on the communicative function of art, an aesthetic value which had its foundation in the May Fourth Movement.

The next significant point was Mao Zedong's "Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Arts and Literature" in 1942 which laid down a theoretical framework for Chinese Social Realist art which called for representational images with positive socialist content or political relevance. The Academic or Literal Realist line was further substantiated when Xu Beihong became the principal of the Beijing Art Academy in 1948 and this was followed by many Soviet Social Realist artists visiting and teaching in China in the 1950s.

The Equator Art Society, founded in 1956, is often associated with Social Realism in Singapore although it was more of a realistic confluence and to some extent a common front reacting to the emerging formalist interest in the 1950s.

The Arts Association of Chinese High School formed earlier appeared to echo more intense political sentiment in its anti-colonial stance:

The independence of Singapore has been brutally denied by the British government. This can only deepen the anguish of Singaporeans and help us apprehend the true feature of the British ruler and strengthen our confidence and determination for independence.... The objectives of our exhibition is to promote patriotism with art works of relevant subject matter and form... and to bring art closer to the masses. [p. 1]

The 1953 Chinese High School Arts Association catalogue contains oils, woodcuts and drawings by Chua Mia Tee, Lim Yew Kuan, Lee Boon Wang and Lai Kui Fang, among others. These artists were later active. in the Equator Art Society which opposed the formalist and newer "Western" trends which were regarded as going against the grain of the development of a national identity in art. This sentiment was voiced in the 1965 Equator Art Society catalogue:

We deeply believe that art, like any other field of study, can only be achieved through constant and serious practice and study. Unfortunately there are artists who are only trying to copy Western art which has not the least of our national flavour. This certainly is not the art that serves to help uphold our national dignity and to help in cur nation building. ["Foreword" 1965]

The Foreword in the exhibition catalogue of the following year stated:

Our art society has been in existence for ten years. Throughout this rather long period, we have come to realise that the development of the genuine school of art is a tedious and painstaking journey and also an arduous and endless struggle. Only those indefatigable artists who, having known the value of the genuine school of art, can push their way out in this society which is fraught with the temptation to personal aggrandisement in all its devilish forms. The value of the genuine school of art lies in the fact that it does not lose its integrity amidst the ugly commercial dealings belonging to the decadent bourgeois. Instead, it always works to faithfully reflect or expose the very root of the reality of life, to spread the Truth, the Virtue, and the Beauty of this world.

Chua Mia Tee's National Language Class is charged with anti-colonial nationalistic content and is a fine example of Social Realist work To Chua, who came to Singapore in 1937 and attended NAFA from 1952 to 1957, art must reflect real life. It reed not necessarily be fully naturalistic but it must be firmly grounded in reality, so that the work is in no way ambiguous but rather offers an easily accessible point of reference for the viewer. Workers in a Canteen, a 1974 work, appears to be less charged with ideological content but is a much more complex picture.

Chua Mia Tee's National Language Class is charged with anti-colonial nationalistic content and is a fine example of Social Realist work To Chua, who came to Singapore in 1937 and attended NAFA from 1952 to 1957, art must reflect real life. It reed not necessarily be fully naturalistic but it must be firmly grounded in reality, so that the work is in no way ambiguous but rather offers an easily accessible point of reference for the viewer. Workers in a Canteen, a 1974 work, appears to be less charged with ideological content but is a much more complex picture.

Despite the long history of interest in woodcut in Singapore, the first art exhibition dedicated to the medium was only held in 1966. It featured the work of Lim Yew Kuan, Tan Tee Chid, Lim Mu Hue, See Cheen Tee, Choo Keng Kwang and Foo Chee San (Tan Tee Chie pp. 31-34), most of whom were teachers at NAFA.

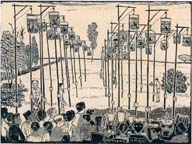

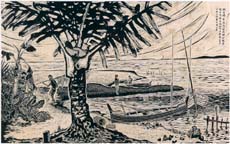

Lim Mu Hue's Chinese Puppet Theatre and Tan Tee Chie's Brobak Birds Competition are realist works depicting facets of life while Seascape is a work whose wood board was jointly engraved by Lim Yew Kuan, Choo Keng Kwarg, Foo Chee San, Koh Chen Ti, Tan Tee Chie and Lim Mu Hue -- a delightful example of collaborative work in Singapore art.

Lim Mu Hue's Chinese Puppet Theatre and Tan Tee Chie's Brobak Birds Competition are realist works depicting facets of life while Seascape is a work whose wood board was jointly engraved by Lim Yew Kuan, Choo Keng Kwarg, Foo Chee San, Koh Chen Ti, Tan Tee Chie and Lim Mu Hue -- a delightful example of collaborative work in Singapore art.

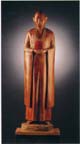

Other notable realist artists in Singapore included Wee Kong Chai who was competent in both painting and sculpture, The Reverend Hong Choon and Mother and Daughter are examples of his very sensitive sculptural works which vividly capture the personalities and relationship of his subjects.

Other notable realist artists in Singapore included Wee Kong Chai who was competent in both painting and sculpture, The Reverend Hong Choon and Mother and Daughter are examples of his very sensitive sculptural works which vividly capture the personalities and relationship of his subjects.

Apart from the Social Realists, there were many artists painting in the realist mode. Ho Kok Hoe, who was for many years president of the Singapore Art Society, was one such. Conversation is one of his oft-reproduced works.

Chinese High School Arts Association. Foreword by director, exhibition catalogue, 1953.

Equator Art Society. "Foreword". Catalogue of society's 4th exhibition, 1965.

Equator Art Society. "Foreword". Catalogue of society's 5th exhibition, 1966.

Tan Tee Chie. "Xinjiapo diyige muke zhan" in Shyue Dah Annual Magazine. Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts.

Last updated: May 2000