This document is part of a joint project of the Singapore Art Museum and the Honours Core Curriculum, National University of Singapore. This image and accompanying text appears here with the kind permission of the Singapore Art Museum.

Another pillar of Singapore art in the 1930s, formed as part of the proliferation of modern art education in China according to May Fourth aesthetics, is the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). Established in 1938, three years after the Society of Chinese Artists, the Academy was initiated by the Singapore alumni of Jimei School in Xiamen.

Penang-based artist Yong Mun Sen, who lived in Singapore during the late-191Os, was amongst those who proposed an art academy in Singapore (Yeo Mang Thong, pp.71-5), but it is widely recognised today that the founder of NAFA was Lim Hak Tai, a teacher at the Xiamen Academy of Art and Jimei Teachers Training College before initiating NAFA in Singapore. There is a Portrait of Lim Hak Tai by Xu Beihong painted in 1939 in the Singapore Art Museum collection.

Penang-based artist Yong Mun Sen, who lived in Singapore during the late-191Os, was amongst those who proposed an art academy in Singapore (Yeo Mang Thong, pp.71-5), but it is widely recognised today that the founder of NAFA was Lim Hak Tai, a teacher at the Xiamen Academy of Art and Jimei Teachers Training College before initiating NAFA in Singapore. There is a Portrait of Lim Hak Tai by Xu Beihong painted in 1939 in the Singapore Art Museum collection.

The Chinese art academies were the models for NAFA and, in its initial years, its lecturers were almost entirely graduates of art academies in Shanghai, Beijing, Xiamen and Paris. It is interesting to note that as much as Singapore was a receptor from the Chinese art academies in north and south China, the modern educational institutions in the Xiamen area were largely initiated and funded by overseas Chinese, including those in Singapore. The curriculum was divided into Western oil painting (Academic Realism and the School of Paris in its Post-impressionist, Symbolist and Fauvist aspects) and traditional Chinese ink painting.

The dichotomy of Western and Chinese art traditions in the Shanghai art school curriculum was repeated in NAFA in Singapore. Amongst the early ink painting teachers at the academy were Lu Heng, Wu Tsai Yen and See Hiarg To. Wu Tsai Yen studied at Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts from 1931 to 1934 and specialises in finger painting. The pine tree, an evergreen and a symbol of longevity, is a favourite subject of Chinese art. Wu has captured the various nuances of a solitary Pine Tree, contrasting the texture, strength and tenacity of the trunk with the softness and delicacy of the leaves.

The dichotomy of Western and Chinese art traditions in the Shanghai art school curriculum was repeated in NAFA in Singapore. Amongst the early ink painting teachers at the academy were Lu Heng, Wu Tsai Yen and See Hiarg To. Wu Tsai Yen studied at Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts from 1931 to 1934 and specialises in finger painting. The pine tree, an evergreen and a symbol of longevity, is a favourite subject of Chinese art. Wu has captured the various nuances of a solitary Pine Tree, contrasting the texture, strength and tenacity of the trunk with the softness and delicacy of the leaves.

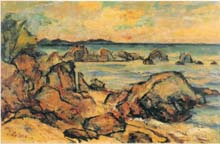

Amongst the early Western art teachers at the academy were Chong Pai Mu and Chen Jen Hao whose respective works Fish and Rocky Coast are illustrated here.

Amongst the early Western art teachers at the academy were Chong Pai Mu and Chen Jen Hao whose respective works Fish and Rocky Coast are illustrated here.

NAFA may be seen as a manifestation of the proliferation of art education in China, a trend driven by the new communicative aesthetics which required a formal (i.e., modem classroom education) approach.

The educational philosophy in the early years embraced both Chinese nationalism and Nanyang regionalism as both themes existed concurrently in Singapore before the 1950s, with Chinese nationalism having emphasis before the Sino-Japanese War and Nanyang regionalism thereafter.

In the late 1930s, before and during the Sino Japanese War, Chinese literary efforts in Singapore, inspired by Chinese rationalism, focused on resistanceliterature, The early activities of the Society of Chinese Artists and NAFA were correspondingly centred on wartime efforts in aid of the resistance against the Japanese invasion of China. Nanyang regionalism, on the other hand, refers to a conception of Nanyang, or Southeast Asia, prior to national divisions.

The term "Nanyang Style" first appeared in literary criticism. Relative to the visual arts, literary activity of Singapore Chinese migrants had an earlier beginning with the publication of Xinguomin zazhi, the associate magazine of the daily newspaper Xinguomin ribao in 1919. By the late-1920s, there was a tendency towards vernacularism in literary works. Emphasis was placed on local (Nanyang) subject matter and this gave birth to the term "Nanyang Style". The term was a generic one which was used to characterise the subject matter of such writings, Nanyang Style did not denote a specific aesthetic paradigm as did notions of linguistic vemacularism (as in the May Fourth Movement), Social Realism or aestheticism. In the late-1920s and 1930s, some proponents of the Nanyang Style associated writing with the articulation of a Nanyang/Overseas Chinese identity and took the literary discourse even further to deal with the larger social issue of a Nanyang regionalist culture.

Yeo Mang Thong. Xinjiapo zhanqian huaren meishushi lunji. Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 1992.

Last updated: May 2000