Ensuring Fair Play in Inter-Cultural Encounters

Do we need a Tertium Comparationis? -- A Translator's Perspective

Malcolm P. Williams, King Fahd School of Translation, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetuan, Morocco

The theme of my paper can be summarized as follows. A world of globalization and the Internet is in increasing need of the translator. However, the sort of translation required is far more challenging than simply decoding and re-encoding words from Language A to Language B. In order to fill this expanding role satisfactorily, the translator needs to maintain balance on two axes. First he needs to maintain balance between what A.F. Holmes calls metaphysical objectivity and epistemological subjectivity. Secondly, he needs to maintain the balance of what C.S. Lewis called the Tao, roughly the equivalent of what many people call natural law, but seen as having been divinely planted in the universe. Both of these things are under threat by certain aspects of contemporary culture. I will develop each of these points in the following pages.

1. The Increasing Need for Translators.

One of the results of globalization and ever more rapid and accessible communication is that inter-cultural encounters are becoming increasingly frequent and it is becoming increasingly necessary to take into account multiple audiences. This means that the chances of misunderstanding and reaction against the "other" are manifold. There is perhaps no better place to examine such problematic intercultural encounters as in Morocco, which has historically bridged the gap between Africa and Europe, and stands on the classical sea route between east and west.

As an illustration of the opposing points of view represented, one needs go no further than to note that the characteristic way in which Moroccans referred to the activities of what Europe called the Barbary pirates was as the Holy Sea War. Another example is that of Kate Aidie's much criticized report on the Dunblane massacre. It was, I believe, made initially for an international audience, for which it was eminently appropriate. However, when shown on British domestic television, it was widely criticized for not showing enough emotion. Examples of such problems caused by the conflicting needs of multiple audiences could be multiplied.

2. The Qualities Required of the Translator of the Twenty-first Century.

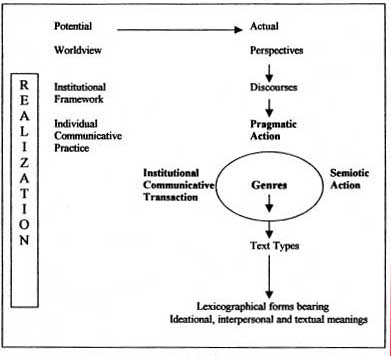

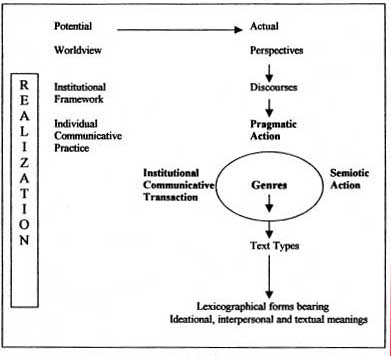

The translator of the twenty-first century needs to work with a model of the translation process that takes into account the historical, cultural, and social context of what he is doing. Such a model is given in Figure 1 below. The focus of the translator's work has to do with genres (novels, scientific and economic reports, poems etc.), which are realized by combinations of text types (narrative, descriptive, expository, argumentative, exhortatory etc.), which in turn are realized by lexicographical forms or words bearing ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings. The genre needs to be seen not in terms of its literary meaning, but in its social context, as a product of certain social circumstances, the defining feature of each genre being its communicative purposes (as argued by Bhatia 1993 p.100). Each genre takes place in the context of a certain institutional communicative transaction, as a result of which it fulfils a certain number of generalized conventional communicative purposes. However, in addition to these conventional purposes, writers and speakers often have certain specific conventional purposes and personal communicative purposes that together constitute the pragmatic action of the text. This pragmatic action takes place within a world of pre-existent micro- and macro-signs (words, phrases, textual patterns, pictures, clothes etc.), where the writer/speaker uses these pre-existent signs for purposes of his own.

However, all this is taking place within a context of patterns of words, or discourses, which are characteristic of particular institutions, and reflect certain worldviews, which determine legitimate objects of knowledge, attribute qualities to these objects of knowledge, and specify legitimate relationships between these objects (Kress 1988:3). Given that no two worldviews are totally different, it is most helpful for the translator to think of worldview as being the totality of an individual's or a society's view of reality, which is in turn made up of "a large number of distinguishable perspectives or paradigms" (Kraft 1989:82). For example, when we compare capitalism and communism as ideologies, we find that they are not totally different, but rather they contain a number of contrasting perspectives within a framework of similar perspectives; while capitalism is conventionally seen as giving pride of place to individual initiative and individual reward, and communism as giving pride of place to the state, both operate largely within a materialist framework (Hatim & Williams 1998:128).

This model takes into account the fact that the translator encounters problems at a number of different levels, not just the linguistic level of finding the correct meaning of a word or finding the appropriate turn of phrase in the language into which he is translating. Here are some Examples of this type of problem.

3. Types of Inter-Cultural Problems Facing the Translator.

3.1. A Problem of Semiotics.

One prickly issue in relations between the Arab world and the West is on the one hand the ignorance which many westerners have about the degree of development that has gone on in the Arab world, and on the other hand the sensitivity that many Arabs feel towards any representation of their culture which confirms the stereotype which Europeans hold. This can lead to problems when one is seeking to represent this culture abroad. For instance, a Moroccan living in the west who comes along by chance to an event where a couscous is being cooked and served in the traditional manner may well be offended and accuse those putting on the event of presenting Moroccan culture as being backward.

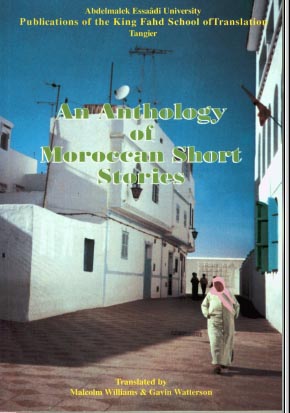

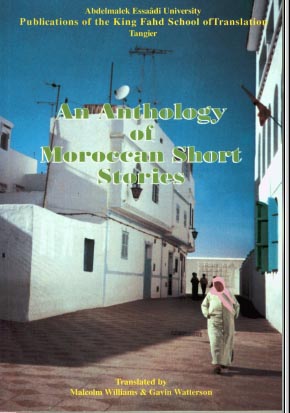

A practical example of where this has affected my work has been in the selection of the cover for the book of short stories that I translated with a British colleague. Bearing in mind the sensitivities involved, we wanted to find a scene that presented the strong traditionalism of Moroccan culture while at the same time showing that modernization is going on apace and that the modern and the traditional coexist side by side. The solution was to select a photograph taken in the Medina of Asileh with a woman dressed in traditional dress with a traditional gateway and a satellite receiver in the background (see Photograph 1 in the Appendix).

3.2. Translating Arabic Direct Speech in Novels.

In translating Arabic novels into English, one of the challenges that the translator frequently faces is how to translate the many greetings, exclamations and idiomatic expressions that occur. Does one totally domesticate them and reduce the religious aspect to that expected by the English-speaking audience, or does one translate them literally, running the risk of so exoticizing the text that it is ridiculed or rejected by the target audience. The third possibility is to hew out a new language expressive of the worldview of Muslims and the comprehensive situation of Arabs, but at the same time accessible to the target audience. In seeking to do this, the translator is fulfilling the role of intercultural communicator and facilitator par excellence. He is developing the capacities of the target language, while at the same time gently stretching the target audience's tolerance for otherness. Some Examples are given in the appendix.

Example 1, "May God curse Satan," is not an expression that we use that often in the west. Many have enough difficulty trying to believe in God. To believe in Satan as well is for most simply beyond the pale. However, we cannot expunge it, for it is woven into the warp and woof of the text, as is shown by the way the speaker continues to begin to argue about who Satan is.

As can be seen from Example 2, the whole worldview of these characters is informed by Islam. The religious language has to be preserved even though it clashes with that of the majority of the western audience. This is because the whole purpose of the book is to glorify the Islamic heritage and the traditional Moroccan identity. However, this does not mean that every religious reference has to be preserved. To preserve the religious tone of Example 3 would be excessive. All the translator needs to do here is to preserve the pragmatic force.

Examples 4-6 are given to show you something of the variety and richness of these expressions. In Example 7 again, we cannot get away from the religious character of the text. The translator is forced to modulate the text somewhat, but its religious character is too active as a productive component of the characters' integral worldview for him to pay too much attention to the audience's sensibilities. The role of the translator here is to modulate the text so that the religious element does not appear overdone. However, his job as a faithful communicator is to maintain the essential otherness of the text.

3.3. The Sultans' Letters.

Translating diplomatic letters of the last century poses another problem. Here the main problem is the need to maintain balance between the needs of historical exoticization and domesticization. However, the problems that concern us particularly here are what to do with the honorific phrases that follow the name of the Sultan (nassarahu allah -- May God bring him victory) and the imprecatory phrase (dammarahum allah -- May God destroy them) that follows the names of every British government representative. One can deal with the honorifics following the name of the Sultan by simply reducing their frequency. However, what should be done with the imprecatory phrases? Are they purely a formality, or do they represent the personal standpoint of the authors of the texts? In either case, the translator needs to play them down so as to avoid an excessively hostile reaction from the western reader, while gently making him aware of the hostile attitude of the Moroccan party. Or are we dealing here with some sort of curse, the inverse of baraka (blessing) which the Moroccan kings are so famous for?

3.4. The Translation of the Word Allah.

One of the most vexed issues is the translation of Islamic religious vocabulary, and in particular the question of whether the word Allah should be translated into the English term God, or whether it should simplified be transliterated. Many members of the Muslim community in Britain insist that it should not be translated, and it is interesting that many of my students at the King Fahd School of Translation feel the same way. In discussing the pros and cons of this, I observe that the choice is pregnant with theological implications. All other things being equal, to translate it implies that the Muslim God and the Christian God are essentially the same, whereas to refuse to translate it implies that the two are essentially different.

However, does this mean that it is appropriate to follow one's theological nose in all texts? It would appear not, for when students try not to translate the term even in legal and administrative texts, the effect is distinctly odd. It distorts the purpose of the texts, for legal texts are not intended to further a particular theological position, but rather to stipulate a law.

What are the criteria for making the choice then? When the writer of the text appears to be making a theological point, then the choice is significant, and the term to be used should be the one most accurately expressing the viewpoint of the writer, although it is a mute point if the translation is free to choose according to his own preference when the position of the writer is not manifest. When the theological point is not at issue, however, the choice to be made should be the unmarked one, the one that most conforms to the norms of the target culture and genre.

The translator is having to decide what the position of the author is, what his intention in that particular text is, and then to make a translation decision depending on whether the word is central to the conventional or personal goals of the author. Considerations of the effect of the word on the audience only come into play when the word is peripheral to conventional and personal goals.

3.5. Ibn Battuta.

So far, the examples given have involved the translator acting as mediator at the level of the text. However, there are Examples where the translator has to act as mediator at a higher level. An example of this is a job I was once given to translate a summary of Ibn Battuta's Rahla that was originally written in Arabic. My skopos was simply to translate the text into English with a view to it being given to visitors to the proposed Ibn Battuta Museum in Tangier. However, it rapidly became clear that the original text itself was unsuitable for the English audience it was intended for. It had, for instance, a long section dealing with his name and genealogy, and it went into detail about his visits to various famous Muslim sheikhs. The summary had been written with the interests of Arab Muslims in mind, and had nothing to appeal to the western reader, even if he had become a Muslim. The ideal solution would have been to write a new summary directly into English with the English audience in mind. However, the sponsors of the work would not consider this. Nevertheless, having made the proposal, my conscience was salved.

More problematic was a sentence that came at the end of a paragraph in the source text in a section about Ibn Battuta's moral character. This is given in Example 8. What is a translator to do with the last sentence of the original? Is this really going to serve to attract the reader to Ibn Battuta? Does such a sentence really express an authoritative Islamic attitude, and even if it does so, is it honouring to Islam in the western context? Here the translator is torn between serving the manifest purpose of the source text, and remaining faithful to the facts asserted in the source text. I will leave it up to my audience to guess how I decided to resolve this problem.

3.6. Arab Argumentation.

The problem of Arabic argumentation is well represented by Example 9. While most would probably agree that a valid point is being made in these paragraphs, it is so overdone that most western readers would probably be repulsed. Should the translator modulate the argument, reducing the level of violence in the lexis, so as to make it more persuasive, or should he leave it as it is. What implications does this have for banner headlines given in tabloid newspapers, which take brief one-sentence extracts from Arab leaders speeches without any regard for the effects on meaning of Arab rhetorical conventions?

3.7. In the Courtroom.

These examples can be extended to include the problems faced by the courtroom interpreter. According to the National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators, the interpreter's oath concerning accuracy is deceptively simple:

The court interpreter should always thoroughly and exactly interpret what is said, omitting nothing and stating precisely what has been said, given the exigencies of grammar and syntax in both languages. [De Jongh: 265ff]

However, no mention is made here to rhetorical variation that is often so crucially important in determining juries' impressions.

4. Balance as a Dominant Concern in Translation Studies.

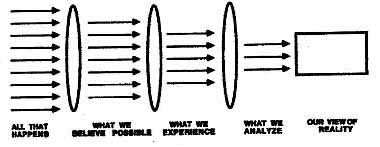

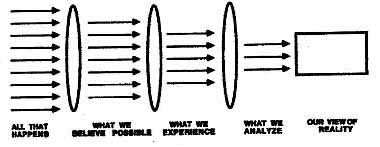

From the above, it can be seen that the translator is faced with a number of problems, not just at the grammatical and structural levels, but also, and far more vitally, at the interpersonal levels. He needs to operate within a framework that enables him to take equally seriously both the content and truth of the message, and the personal and conventional goals of those participating in the communication event. Thus he needs to balance the claims of epistemological subjectivity, and metaphysical objectivity. The history of philosophy faces us with a swing between the two. If the Enlightenment era has been characterized by a search for an absolute to put in the place of God, and by a tendency to totally ignore the observer - or the subject - in the process, most twentieth century philosophical trends have reacted against this in the name of relativism, and have so focussed on epistemological subjectivity that they have neglected metaphysical objectivity. The translator needs a balance between the two, as in Figure 2 below. There is a REALITY (all that happens) to be discovered and explored in its infinitude, but we need to recognize that what we see, feel and understand is only a small part of that, and passed through a number of lenses, including those of belief, experience, and conscious analysis. This is our reality.

Factors influencing our view of reality [Figure 2]

Factors influencing our view of reality [Figure 2]

Secondly, the translator needs to maintain and, if necessary restore, a tertium comparationis. Without such a stable point of reference, the translator will tend either to absolutize his native culture, or the culture to which he is relating (this is probably the real meaning of going native), or a particular value. For the translator, this means that he either becomes a slave to the source text, or surrenders totally to the demands of the target text and culture. Such a tertium comparationis is provided to some extent by the natural world in which all participants in the communication process live, and secondly by the way man is made physically predisposed to certain shapes, and certain ranges of sound waves. However, the translator also needs that balance found within the natural law, or what C.S. Lewis called the Tao, adopting a term from the Far East, which preserves us from the range of fads that buzz so swiftly around the world in the absence of any stable metaphysical framework. As A.M. Wolters puts it:

To see laws of nature and norms as continuous with each other is a confusion of facts and values to the modern mind, a mixing up of the "is" and the "ought". However, the modern mind is exceptional in this view. For all of the divergences among worldviews throughout the history of mankind -- primitive or "higher", cultic or philosophical, pagan or biblical -- nearly all worldviews are united in their belief in a divine world order that lays down the law for both the natural and the human realms. They have called that order many different things -- Tao in the Far East, Maat in ancient Egypt, Ananke and Moira in Greek religion, Logos or form in Greek philosophy, wisdom in the Bible -- but they all have in common the idea of an order to which both mankind and nature are subject. [Wolters 1996: p.16]

Asserting Enlightenment Reason as the basis for such international conventions as The Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead of the Tao is at the root of much Islamic suspicion of them. In both East and West the Tao is being increasingly ignored, undermined by relativism, the deconstruction of the subject and the abandonment of objective reality. Instead of the Tao, we idolize particular values: tolerance, respect for animal life, care of the environment, or even political correctness. Any value viewed from outside the Tao becomes an idol and eventually disintegrates as too much weight is put upon it. The Greek tragedians were on the right track when they viewed a tragedy as the result, not of a particularly bad vice, but as an excess of virtue.

In conclusion, the translator needs to keep considerations of author's intentions, source and target text and audience expectations all in balance, and the only way to do this is through recognizing the legitimate demands of the twin poles of epistemological subjectivity and metaphysical objectivity, and maintaining the balance that is found within the Tao.

Bibliography

Bhatia V.K. (1993) Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. Longman.

Hatim B. (1997 Communication across Cultures: Translation Theory and Contrastive Text Linguistics. University of Exeter Press.

Hatim B. & Williams M.P. (1998) "Course Profile -- Diploma in Translation", The Translator. Vol.4 No.1, St Jerome Publishing.

Hodge R. & Kress G. (1988) Social Semiotics. Polity, Cambridge, UK.

Holmes A.F. (1977) All Truth is God's Truth. I.V.P.

Howe R.L. (1963) The Miracle of Dialogue. Seabury.

Lewis C.S. (1943) The Abolition of Man. 1st edition OUP, reissued by Fount in 1978.

Williams M.P. (1992) "Ideology, Point of View and the Translator", Turjuman. Vol.1, No.1, Ecole Sup&eracute;rieure Roi Fahd de Traduction, Tangier.

Williams M.P. (1997) "Translating the Sultan's Letters: A Study in the Avoidance of Exoticism", Turjuman. Vol.6 No.2, University Abdel Malek Essaadi, Ecole Supérieure Roi Fahd de Traduction, Tangier.

Wolters A.M. (1996) Creation Regained. Paternoster Press.

Last modified: 29 May 2001

Factors influencing our view of reality [Figure 2]

Factors influencing our view of reality [Figure 2]